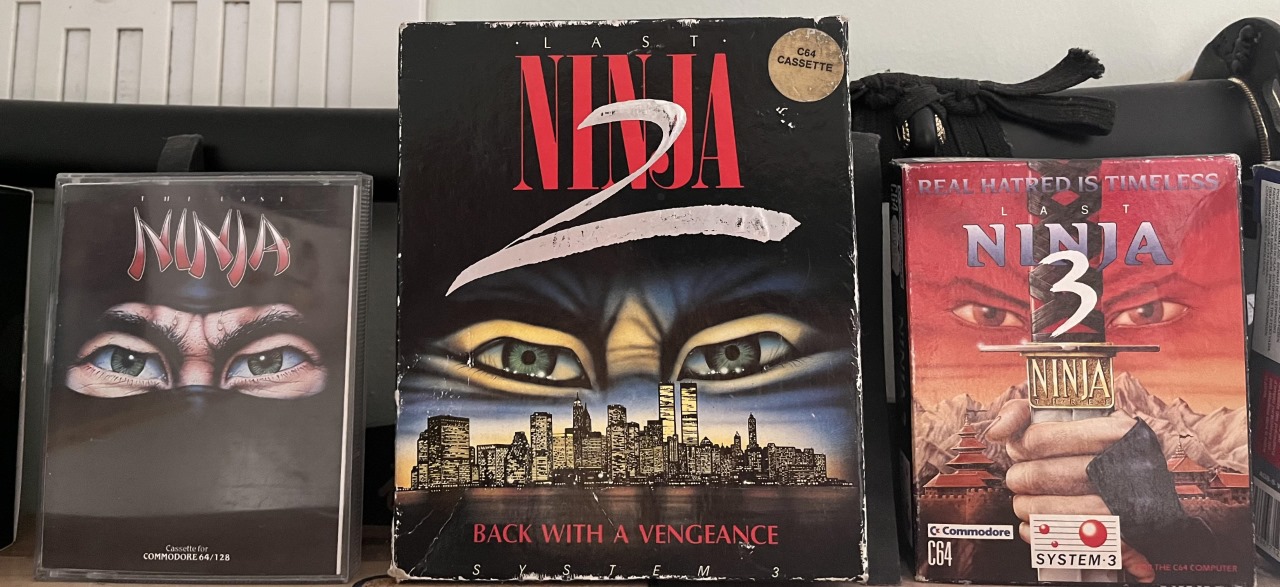

Long before ninjas were mainstream icons in gaming, The Last Ninja series carved out its own legend on the Commodore 64. With its striking isometric visuals, atmospheric music, and cinematic level design, it wasn’t just a game—it was a phenomenon. It blurred the lines between genres, blending action, exploration, puzzle-solving, and a touch of mysticism, all wrapped in a slick ninja aesthetic. To those who lived through the late '80s era of 8-bit gaming, The Last Ninja was more than just another title on a cassette tape—it was the closest thing to playing a martial arts movie.

The series gained notoriety for its visual style and revolutionary mechanics, but it also earned respect for its brutal difficulty and artistic ambition. Developed by System 3, a studio that always seemed to think beyond the limits of the hardware, the trilogy (and the ghost of a fourth installment) became synonymous with quality, innovation, and unforgiving gameplay. Every entry in the series built on what came before, offering not just new levels, but completely new moods and contexts—from ancient Japan to modern-day New York.

Even today, more than three decades later, The Last Ninja series is remembered not just for its gameplay, but for its identity. This wasn’t a game that held your hand. It threw you into the shadows with nothing but your reflexes and your wits, demanding trial, error, and ultimately mastery. And if you managed to survive its traps and trials, you didn’t just win—you earned it.

The Origins of The Last Ninja Series

When The Last Ninja hit the Commodore 64 in 1987, it wasn’t just another game in the growing library of martial arts-themed titles. It was a technical marvel. Created by System 3, under the creative direction of Mark Cale, the game's goal was simple but ambitious: create the first isometric action-adventure game to mix puzzle-solving, exploration, and combat—wrapped in a cinematic martial arts world.

At the time, the Commodore 64 wasn’t exactly known for handling complex 3D environments. But programmer John Twiddy and graphic artist Hugh Riley managed to pull off an isometric engine that gave players the illusion of depth and dimension in a mostly 2D gaming world. It was no small feat. They used clever sprite layering, character rotation mechanics, and optimized color palettes to craft environments that felt alive—lush gardens, dark dungeons, bamboo forests, and ritual shrines, all rendered in surprisingly rich detail.

What truly set the game apart was its identity. This wasn’t just another side-scrolling beat-'em-up. It had pacing. You had to think. Sometimes, the hardest enemy wasn’t a guard—it was a jump across a broken bridge or a puzzle locked behind obscure visual cues. You didn’t just run through levels; you unraveled them.

The design philosophy was unusual for its time: challenge the player visually, mechanically, and intellectually. The team intentionally built a game that required patience and persistence. It was an experience that demanded attention and rewarded mastery. And in doing so, System 3 created something that felt far more cinematic than its contemporaries—more like an experience than a game.

Gameplay Mechanics and Series Design

At the core of The Last Ninja trilogy was a gameplay system that, even today, feels unique. The isometric perspective wasn’t just a visual gimmick—it was integral to the experience. Every action, from combat to exploration, had to be rethought within the context of diagonal movement. It turned what could’ve been a simple action game into a complex navigational and spatial challenge.

The controls were, at best, polarizing. Movement relied on an eight-directional control scheme that felt more natural on a joystick than a keyboard. Every corner you turned or ledge you leapt had to be approached at an angle—meaning even basic platforming could lead to disaster. For many players, just getting Armakuni across a river without drowning was an achievement unto itself. This level of difficulty wasn’t a bug—it was the design. The controls forced players to slow down and approach each screen as a puzzle.

Combat, too, was layered. Unlike the button-mashing action games of the time, The Last Ninja made you use timing and spacing. Enemies could be engaged high, mid, or low, and you'd often have to switch stances to block or strike effectively. And with a limited health pool, every mistake was costly. Weapons varied depending on the level and title—ranging from basic punches and kicks to swords, staffs, throwing stars, and nunchaku.

But the series wasn’t all combat and acrobatics. Puzzle-solving was deeply embedded into the progression. You had to find items, combine them, and sometimes use them in obscure ways—often with minimal visual or narrative cues. Whether it was locating a key hidden in the environment or using an object in a seemingly unrelated location, exploration and experimentation were key. In this way, The Last Ninja series played more like an action-adventure hybrid long before that became a common genre label.

It was a demanding design philosophy—one that turned off impatient players but enchanted those who embraced its logic.

The Last Ninja (1987)

The first entry in the series set the tone in more ways than one. Released in 1987 for the Commodore 64, The Last Ninja introduced players to Armakuni, the titular "last ninja," whose clan had been slaughtered by the evil shogun Kunitoki. The game takes place in feudal Japan, where Armakuni embarks on a solitary mission of vengeance through six increasingly dangerous levels.

The environments were impressively diverse for an 8-bit game. You began in The Wilderness, passed through gardens, palaces, dungeons, and finally into the inner sanctum of your enemy. Each zone had its own color palette and mood, helping create a sense of place that far exceeded what the hardware should’ve been capable of.

Each screen felt handcrafted, with enemies placed strategically and items hidden just subtly enough to be missed by careless players. The music by Ben Daglish and Anthony Lees became an instant classic. Each level had its own theme, and the tracks were both haunting and energetic—blending Eastern instrumentation with Commodore 64’s SID chip magic.

The game’s difficulty became both its curse and its charm. While the isometric controls made basic navigation feel like a high-wire act, it was also what created tension. Even a simple jump over a stream felt loaded with peril. Combat was challenging but fair, and the satisfaction of landing a perfectly-timed strike was tangible.

Critical reception was enthusiastic. Reviewers praised the graphics, sound, and ambition of the game. Some critiqued the controls, but most acknowledged they were part of what made The Last Ninja feel so unique. It wasn’t just a game—it was a test of will. And for many players, finishing it felt like mastering a martial art in itself.

Last Ninja 2: Back with a Vengeance (1988)

The sequel, released just one year later, took a bold risk—it transported the game from feudal Japan to modern-day New York City. It was a decision that, at the time, could have easily alienated fans. But somehow, Last Ninja 2 made it work. Armakuni, through a mysterious time portal, finds himself in the 20th century, continuing his battle against the reincarnated Kunitoki.

The new setting opened up a host of possibilities, both visually and thematically. Instead of shrines and forests, players now explored Central Park, office buildings, sewers, and a high-rise mansion. This shift allowed the designers to experiment with new visual motifs—neon lights, concrete textures, and modern machinery—all rendered in the same detailed isometric engine.

Combat remained largely unchanged, but the animations were smoother, and hit detection was slightly improved. Weapon variety expanded with urban flair—nunchaku, throwing stars, and metal pipes replaced the traditional swords. Movement was still tricky, but it felt a touch more refined compared to its predecessor.

The music, composed this time primarily by Matt Gray, was arguably the highlight of the entire series. Tracks like “Central Park Loading” and “The Mansion” became cult favorites. The blend of catchy basslines, ambient synths, and complex melodies pushed the Commodore’s SID chip to its limits. Many fans still rank this as one of the best C64 soundtracks of all time.

Last Ninja 2 was a massive commercial hit. It outsold the original, received strong critical praise, and expanded the fanbase significantly. Ports were made for systems like the NES, Apple II, and Amiga—each with varying degrees of quality. The game’s box art, cassette design, and even loading screens became iconic in their own right.

If The Last Ninja proved the concept, Last Ninja 2 perfected it. It brought cinematic scope, tighter design, and a bold creative leap that paid off. It didn’t just feel like a sequel—it felt like a full-scale evolution.

Last Ninja 3: The Final Battle? (1991)

By the time Last Ninja 3 arrived in 1991, expectations were enormous. The gaming landscape had begun to shift—16-bit consoles were taking over, and new franchises were challenging old ones. Last Ninja 3 was System 3’s answer to the changing times: a game that looked sharper, played faster, and returned to the series’ spiritual roots.

Gone was the modern-day urban setting. Last Ninja 3 brought Armakuni back to a more mystical, timeless world—one that fused Eastern temples with dark fantasy aesthetics. The narrative was simpler and more symbolic this time: Armakuni embarks on a final pilgrimage, overcoming elemental trials—Earth, Water, Fire, Air, and finally, Spirit—to attain ultimate mastery and enlightenment.

The game’s graphical overhaul was immediately apparent. Sprites were larger and more detailed, animation was smoother, and background textures had a more painterly feel. Every level was rich with visual contrast—from sun-drenched monasteries to eerie flame-lit caverns. The isometric view remained, but the environments felt more vertical, complex, and ambitious than before.

Combat saw a few tweaks. Weapon switching was more intuitive, and enemy AI slightly more reactive. However, the controls still carried that trademark clunkiness—precision remained a double-edged sword, especially when navigating tight jumps or narrow ledges. New traps were introduced, adding a heightened sense of danger. One wrong step could send you plummeting to your death or backtracking through entire segments.

Musically, Last Ninja 3 kept pace with its predecessors. Composers Reyn Ouwehand and Rob Hubbard contributed tracks that felt cinematic and immersive. While the melodies may not have reached the iconic status of Matt Gray’s LN2 work, the sound design was richer, more ambient, and tonally appropriate to the spiritual theme of the game.

Reception was mixed to positive. Some critics felt it was a worthy swan song to the trilogy—polished, atmospheric, and challenging. Others argued it lacked the innovation of Last Ninja 2 and relied too heavily on established formulas. Still, for fans, it was a fitting farewell. Last Ninja 3 didn’t reinvent the wheel—but it gave closure to one of the most iconic trilogies in 8-bit and 16-bit gaming.

The Lost Sequel: Last Ninja 4

If there’s one entry in the series that looms like a shadowy legend, it’s Last Ninja 4. Technically, it never existed—at least not in any complete, released form. But that hasn’t stopped decades of speculation, teases, and behind-the-scenes drama from turning it into one of retro gaming’s most fascinating “what ifs.”

After the success of Last Ninja 3, System 3 announced plans for a fourth game that would leap into the 3D era. Early concepts imagined a fully polygonal world, with Armakuni rendered in dynamic third-person, capable of scaling cliffs, climbing walls, and engaging in real-time combat. The environments were set to be larger, richer, and fully explorable. It sounded ambitious, even revolutionary for its time.

And that’s where it all unraveled. Development stalled. The 3D engine proved difficult to manage, budgets ballooned, and the gaming landscape evolved faster than System 3 could keep up. Multiple announcements were made throughout the late '90s and early 2000s—each promising that Last Ninja 4 was “coming soon.” Screenshots were leaked. Trailers were teased. None of it ever saw the light of day.

Some prototypes and builds supposedly existed—shown only at industry expos or locked away on developer hard drives. Fan forums have dissected every shred of evidence, trying to piece together what Last Ninja 4 might’ve been. And while some assets and design notes have surfaced, the game itself remains vaporware.

In 2003 and again in 2007, System 3 once more floated the idea of a reboot—either for PlayStation or mobile platforms. But nothing materialized. Today, Last Ninja 4 is a symbol of what could have been—a final chapter that was never written.

And yet, the myth endures. For fans, Last Ninja 4 remains the series’ white whale, a whispered legend that might someday return, reborn from the shadows.

Audio and Visual Evolution

It’s impossible to discuss The Last Ninja series without diving into its audio-visual brilliance. The franchise was a showcase of how much artistic expression could be squeezed out of limited hardware—especially on the Commodore 64.

The series’ signature isometric graphics were groundbreaking. In an era when most games scrolled horizontally or vertically, The Last Ninja delivered static, multi-layered screens with depth, perspective, and texture. Every level was hand-crafted, with rich use of color and shadow that made environments feel immersive despite their grid-based limitations. From the bamboo groves of the first game to the urban grime of Last Ninja 2 and the elemental backdrops of Last Ninja 3, the visual artistry was consistent and stunning.

But if the visuals drew players in, it was the music that made them stay.

Ben Daglish and Anthony Lees set the tone in the original, creating compositions that felt both ethereal and electric. Then came Matt Gray with Last Ninja 2, whose soundtrack is still heralded as one of the best ever composed for the SID chip. His work demonstrated that game music could be more than background noise—it could be an emotional driver. With tracks that ranged from upbeat to haunting, Gray elevated the game’s mood in a way rarely seen in the 8-bit era.

Last Ninja 3 brought more ambient, mature compositions from Reyn Ouwehand and Rob Hubbard, embracing a more atmospheric soundscape. These tracks reflected the game's mystical tone, using layered instruments and slower rhythms to build tension and mystery.

Across all three titles, the soundtracks weren’t just good—they were iconic. They’ve been re-recorded, remixed, and performed live by orchestras. In the retro music community, The Last Ninja series remains a gold standard for what game music can achieve.

Platform Releases and Key Differences

While the Commodore 64 was the series’ primary platform and home turf, The Last Ninja made its way to a surprising number of systems—each with its own quirks, benefits, and drawbacks.

The Amiga versions featured sharper visuals and smoother animations, but some fans felt they lacked the raw charm and grit of the C64 original. The SID chip’s unique sound couldn’t be replicated easily, and while the Amiga had better audio fidelity, it lacked that nostalgic synth bite. Still, the Amiga ports were widely praised and helped expose the series to a broader European audience.

The Apple II and DOS versions were functional but stripped-down, losing some of the visual flair in the conversion process. Controls often felt laggier, and the absence of smooth scrolling or fluid animation hurt the overall experience.

One of the most controversial ports was the NES version of Last Ninja 2. While it introduced the game to console players, it also stripped out many of the original’s features, including full isometric depth, sound quality, and responsive controls. NES players got a glimpse of The Last Ninja, but not the full experience.

The ZX Spectrum and Atari ST ports varied wildly in quality. Some were beautifully adapted, others were plagued by slowdown, missing music, or reduced visual clarity. It was the wild west of home computer ports—and players’ experiences differed greatly depending on which version they had access to.

What’s clear, though, is that The Last Ninja was ambitious in its platform reach. It wasn’t just a C64 gem—it was a multi-platform legacy, one that connected different player communities under the banner of ninja justice and pixelated punishment.

Fan Culture and Preservation

Though the original trilogy ended over three decades ago, The Last Ninja never truly faded. It’s survived thanks to an incredibly passionate fan base—one that has gone above and beyond to preserve, celebrate, and even rebuild the series for modern platforms.

From SID tune remixes to orchestral reimaginings, the music continues to live on in online communities and live performances. Fans have meticulously archived game files, manuals, and cover art. Emulators have made it easier than ever to play all three games today, complete with save states that soften the notorious difficulty.

Several ambitious fan projects have sought to remake the original trilogy using modern engines. Indie developers have attempted to create spiritual successors, drawing on the isometric puzzle-combat formula that The Last Ninja pioneered. Mods, pixel art homages, YouTube retrospectives—all these efforts show that the series has left an enduring mark.

Even game historians and journalists continue to rank it highly among the greatest Commodore 64 games ever made. Forums like Lemon64, Reddit’s r/Commodore, and YouTube channels devoted to retro content keep the legend of Armakuni alive.

And perhaps that’s the true legacy. The Last Ninja games weren’t just great for their time—they were memorable. They stuck with players. They made them struggle, learn, and eventually triumph. And in doing so, they carved their names into gaming history—not with flashy gimmicks, but with style, substance, and swordplay.

Challenges and Limitations

As legendary as The Last Ninja series was, no retrospective would be complete without acknowledging the cracks beneath the surface. These were not perfect games—far from it. Part of their enduring mystique comes from how they balanced brilliance with frustration, rewarding players with memorable experiences but often demanding patience and persistence far beyond the norm.

One of the most infamous aspects was the control scheme. Even by 1980s standards, movement in the Last Ninja games could be described as clunky at best, and downright punishing at worst. The isometric perspective—although beautiful—often worked against players when it came to precision movement. Basic actions like jumping across small gaps or navigating narrow walkways required perfect diagonal input, which wasn't always easy to execute using the eight-way joystick or keyboard. One missed angle, and Armakuni would plunge into a pit, drown in a river, or walk directly into enemy fire.

Then there was the combat. While it introduced vertical targeting (high, mid, low), which was innovative, it was also inconsistent. Hit detection could feel unreliable. Enemies would sometimes strike before your attack had registered, forcing you to restart sequences due to losing too much health in one bad encounter. Combine that with the fact that many levels only provided limited healing options, and the game often became more about cautious pixel-hunting than fluid combat mastery.

The puzzle design was another divisive element. On one hand, the integration of logic-based challenges made the games feel deeper than your average beat-em-up. On the other, the solutions were often so obscure—especially without text hints—that players had to rely on trial and error or walkthroughs. Important items could be hidden in poorly marked locations, requiring pixel-perfect interaction to pick them up.

Difficulty balancing across the trilogy varied. The first game set the bar high, but by Last Ninja 3, many players felt the challenge had shifted from clever design to artificial lengthening through trial-and-error segments. The lack of save points or continues (in most versions) meant that even experienced players had to replay massive chunks of the game when a mistake was made near the end.

But perhaps the most glaring limitation wasn’t in the games themselves—it was in how they aged. As gaming evolved into more user-friendly, accessible experiences, the Last Ninja series stood frozen in time. For modern players, jumping into these games without guidance can be alienating. The control schemes feel archaic, the learning curve brutal, and the feedback minimal.

Still, these flaws haven’t tarnished the series’ reputation. If anything, they’re part of its mythos. The games were challenging not just technically but spiritually. You didn’t just beat The Last Ninja—you conquered it. And that’s a rare kind of legacy.

From Shadows to Legend: Why The Last Ninja Still Matters

Even decades after its final release, The Last Ninja remains etched in the minds of retro gamers—not just as a technical triumph, but as a game that demanded something deeper from its players. It wasn’t just about reflexes or puzzle-solving. It was about perseverance. Every awkward jump, every brutal encounter, every cryptic item usage was part of a larger journey—one that mirrored Armakuni’s quest for honor, mastery, and redemption.

The trilogy dared to be cinematic before gaming had figured out how to be cinematic. It blended action and atmosphere with a sense of solitude that made each level feel personal. You weren’t just playing a game—you were surviving an ordeal, meditating between sword fights, and unlocking secrets with your mind as much as your blade. The haunting melodies, the layered environments, the stoic protagonist—they all combined into something that transcended the sum of its parts.

Even now, when players revisit the series via emulators or fan-made remakes, that old sense of mystique still lingers. Few games today are willing to let silence, stillness, or difficulty speak so loudly. Fewer still dare to frustrate the player so deeply, only to reward them with genuine triumph.

In a time when games are often polished to perfection and spoon-fed to players, The Last Ninja stands as a relic of an era when success had to be earned. And perhaps that's why it still resonates—because it reminds us that in both gaming and life, the path of the ninja is not the easiest… but it is the most unforgettable.

The Last Ninja Series – Game Details

-

Genre: Action-adventure, Isometric Beat ’em up

-

Release Years:

-

The Last Ninja – 1987

-

Last Ninja 2: Back with a Vengeance – 1988

-

Last Ninja 3 – 1991

-

-

Platforms: Commodore 64, Amiga, Atari ST, MS-DOS, Amstrad CPC, ZX Spectrum, BBC Micro, Acorn Electron, NES (as The Last Ninja)

-

Modern Availability:

-

PC (via emulation or C64 collections)

-

Unofficial online emulators and fan restorations

-

-

Developer: System 3

-

Publisher: System 3, Activision (in some regions)

-

Game Engine: Proprietary isometric scrolling engine

-

Age Rating: Unrated (pre-ESRB)

-

Player Modes: Single-player

-

Awards/Nominations:

-

Multiple Game of the Year awards (C64 magazines)

-

Considered one of the greatest Commodore 64 franchises of all time

-