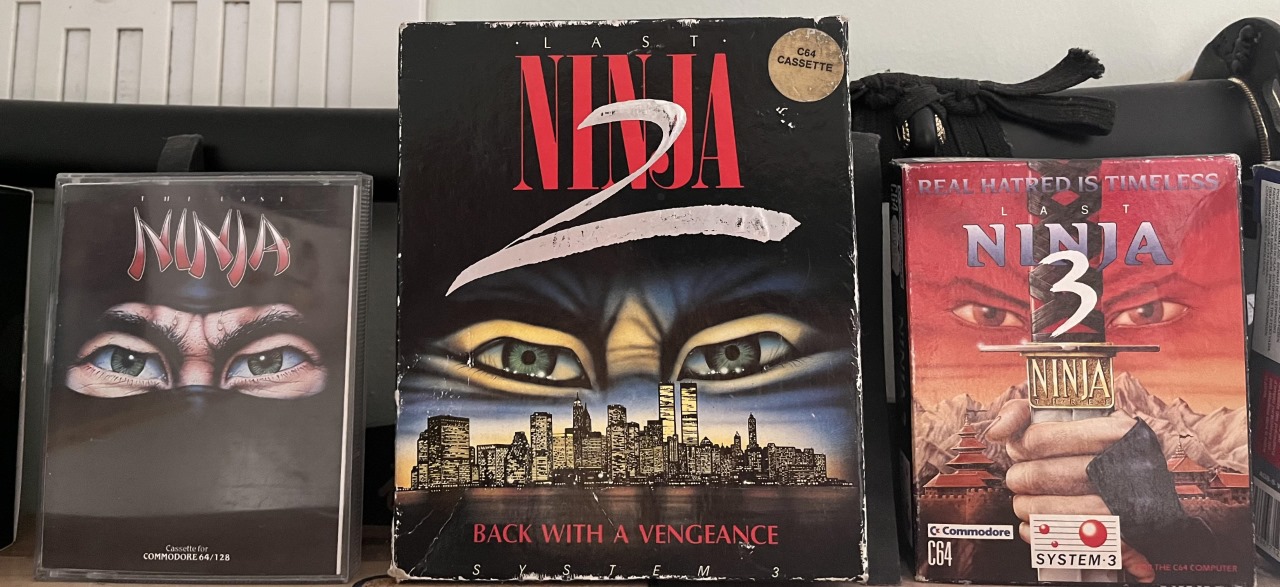

Long before ninjas were mainstream icons in gaming, The Last Ninja series carved out its own legend on the Commodore 64. With its striking isometric visuals, atmospheric music, and cinematic level design, it wasn’t just a game—it was a phenomenon. It blurred the lines between genres, blending action, exploration, puzzle-solving, and a touch of mysticism, all wrapped in a slick ninja aesthetic. To those who lived through the late '80s era of 8-bit gaming, The Last Ninja was more than just another title on a cassette tape—it was the closest thing to playing a martial arts movie.

The series gained notoriety for its visual style and revolutionary mechanics, but it also earned respect for its brutal difficulty and artistic ambition. Developed by System 3, a studio that always seemed to think beyond the limits of the hardware, the trilogy (and the ghost of a fourth installment) became synonymous with quality, innovation, and unforgiving gameplay. Every entry in the series built on what came before, offering not just new levels, but completely new moods and contexts—from ancient Japan to modern-day New York.