In the early 1990s, the gaming world was flooded with mascots trying to capture the magic of Sonic and Mario. But nestled quietly among them was a green amphibian with a crown, a cape, and a surprisingly rich sense of humor—Superfrog. Released in 1993 by the British developers at Team17, this game wasn’t just another mascot platformer. It was, in many ways, a love letter to the Amiga scene—a platform known more for its depth than its flash.

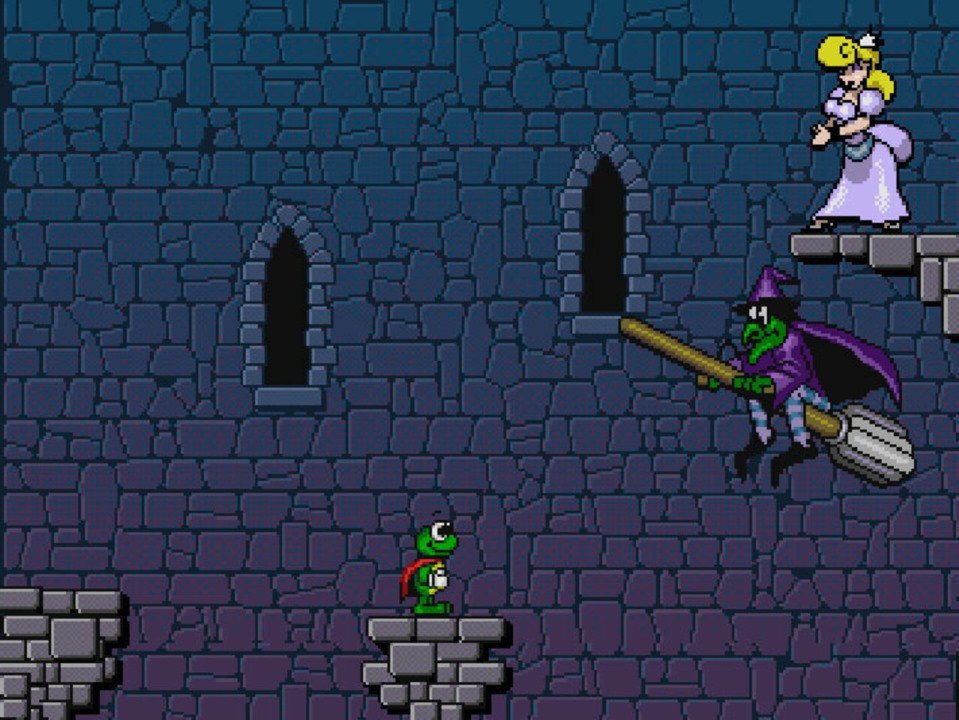

What made Superfrog stand out wasn’t just its responsive controls or colorful visuals—it was how it blended charm, challenge, and playfulness without trying too hard to be “cool.” It didn’t rely on attitude or edgy humor like some of its contemporaries. Instead, it leaned into whimsy. The story was simple: a prince turned into a frog by an evil witch must navigate six worlds to rescue his princess. Classic setup. But the delivery? Fast-paced levels, hidden areas, power-ups galore, and a soundtrack that wormed its way into your brain.

Amiga gamers at the time were used to technical marvels, but Superfrog felt different. It had polish. It felt deliberate. It was clearly inspired by the likes of Sonic the Hedgehog—especially in how it handled momentum and speed—but it layered that with exploration and secret-hunting more akin to Mario. The result? A game that wasn’t quite like either, but managed to borrow the best from both. In retrospect, Superfrog became more than just a solid platformer—it became a point of pride for Amiga players, proof that their machine could produce mascot magic, too.

From Worms to Frogs: Team17’s Leap into Platformers

Team17 was already carving out a name for itself in the early ’90s, but it hadn’t yet become the household name it would be after Worms took the world by storm. Superfrog marked a crucial phase in the studio’s early history—a deliberate attempt to break into the highly competitive platformer market dominated by consoles. And unlike many other Amiga developers, they didn’t cut corners. This wasn’t a rushed or lazy mascot attempt—it was a focused, passionate project built to showcase the strengths of the Amiga platform.

The game was developed using Blitz Basic and pushed the Amiga’s hardware impressively, running at a smooth frame rate with detailed sprite animations, layered backgrounds, and fast-scrolling environments. It felt like a game designed by people who loved the hardware. Designer Rico Holmes and programmer Andreas Tadic worked closely on crafting tight, responsive controls that could rival anything on a Sega or Nintendo system. Their efforts paid off in spades—the game felt fluid, energetic, and alive.

One of the most distinctive aspects of Superfrog’s development was its refusal to simply imitate. Sure, the speed and level loops echoed Sonic, but Team17 avoided the cocky mascot formula. Superfrog wasn’t rude. He didn’t wear sunglasses or crack wise. He just... jumped. And he did it really, really well. The development team focused on building a world that was vibrant but grounded, comical but not chaotic.

From a development standpoint, Superfrog was more than just a technical success—it was a cultural one. It proved that the Amiga wasn’t just a productivity machine with a few games tacked on. It could compete in the mainstream gaming world, with titles that were just as fun, flashy, and functional as anything on a console.

Smooth, Speedy, and Surprising: What Made Superfrog Tick

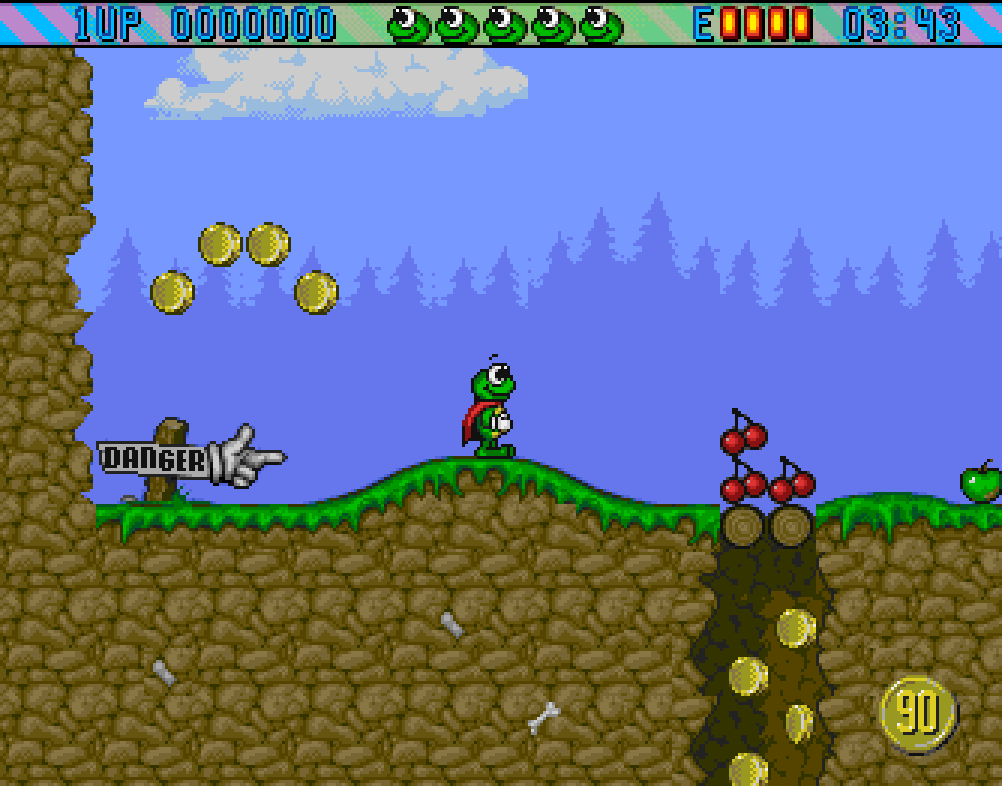

The moment you load up Superfrog, it hits you—the bounce, the fluidity, the unexpected weight of the movement. Unlike many Amiga games at the time, Superfrog nailed its controls with an intuitive feel that required almost no adjustment. This wasn’t a floaty, imprecise platformer. Every jump, bounce, and midair direction change felt responsive and satisfying, thanks to incredibly well-tuned physics and smart level layout.

The gameplay loop was deceptively simple: collect coins, find hidden paths, avoid hazards, and get to the exit before time runs out. But it was the flow—the way the frog zipped through tight corners, ricocheted off trampolines, slid down slopes, and navigated loops—that made it addictive. Unlike Sonic, which punished you with instant deaths for moving too quickly without memorizing level layouts, Superfrog allowed for speed and exploration to coexist. If you took your time, there were secrets everywhere. If you rushed, the levels rewarded memorization and timing.

Power-ups added another layer of strategy. Potions could grant temporary flight or invincibility. Fruit and items increased your score, which mattered not just for bragging rights, but for unlocking the end-of-level bonus game—an old-school slot machine that gave you extra lives and power-ups for future runs.

It’s also worth mentioning how surprisingly large each level felt. You weren’t simply running left to right. There were vertical segments, sprawling secret chambers, and detours that begged to be explored. It turned what could’ve been a quick 10-minute session into a longer, richer experience. Superfrog wasn’t just a fast frog—it was a clever one.

The Prince, the Witch, and the Frog

For all its tight controls and colorful worlds, Superfrog didn’t forget the importance of story—however simple it might’ve been. At the heart of it was a classic fairy tale twist: a noble prince is turned into a frog by an evil witch who also kidnaps his princess. A bottle of Lucozade (yes, the actual drink, cheekily included through product placement) gives the frog superpowers, and thus begins his quest to save his beloved.

What set the story apart wasn’t complexity—it was delivery. The game opened with a beautifully animated intro cutscene that combined cartoon charm with dry British humor. There were no overlong monologues or overwrought drama—just a clean, cheeky setup for an adventure that didn’t take itself too seriously.

Each world maintained that fairytale quality, though filtered through various themes. From Enchanted Forests to spooky castles, from circus tents to ancient pyramids, each new setting reflected a whimsical logic that fit the narrative’s playful tone. You weren’t fighting for survival or glory. You were a determined little frog with a cape and a cause—and the levels made you feel like a fairytale hero on a very animated journey.

The princess—while not heavily featured after the intro—gave the quest a clear goal. There was no convoluted lore or endless exposition. Just a frog on a mission, powered by Lucozade, leaping through the countryside with style. It sounds silly, but it worked. It was sincere, self-aware, and joyful in a way that still resonates.

Colorful Worlds: From Forests to Castles

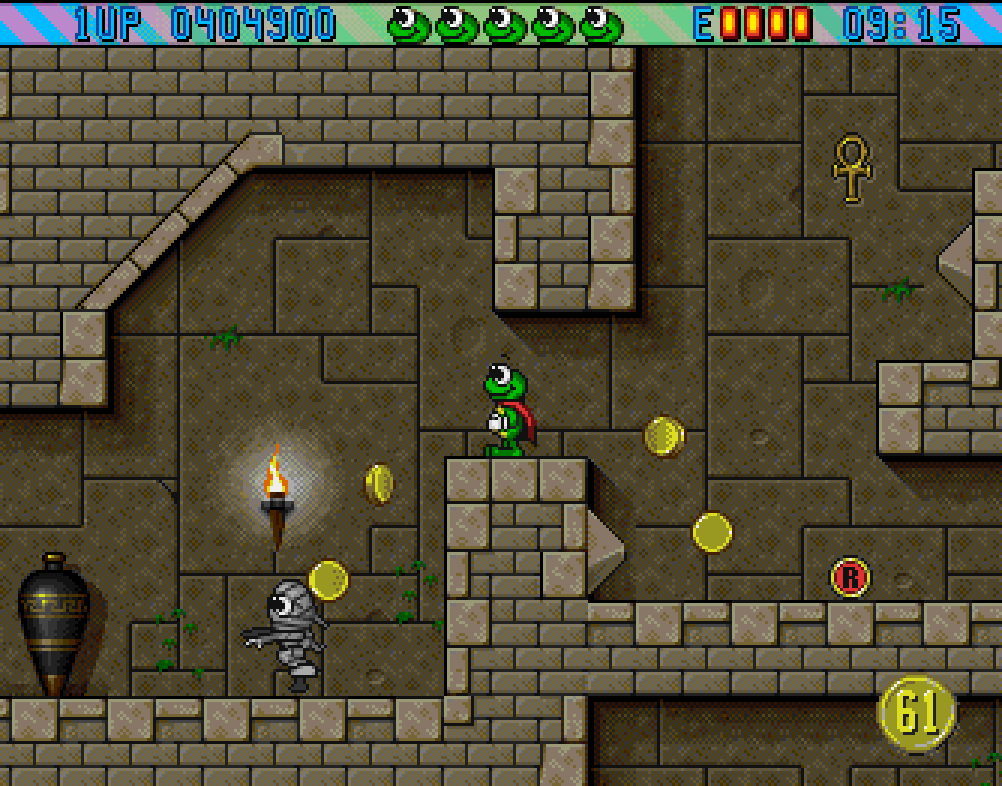

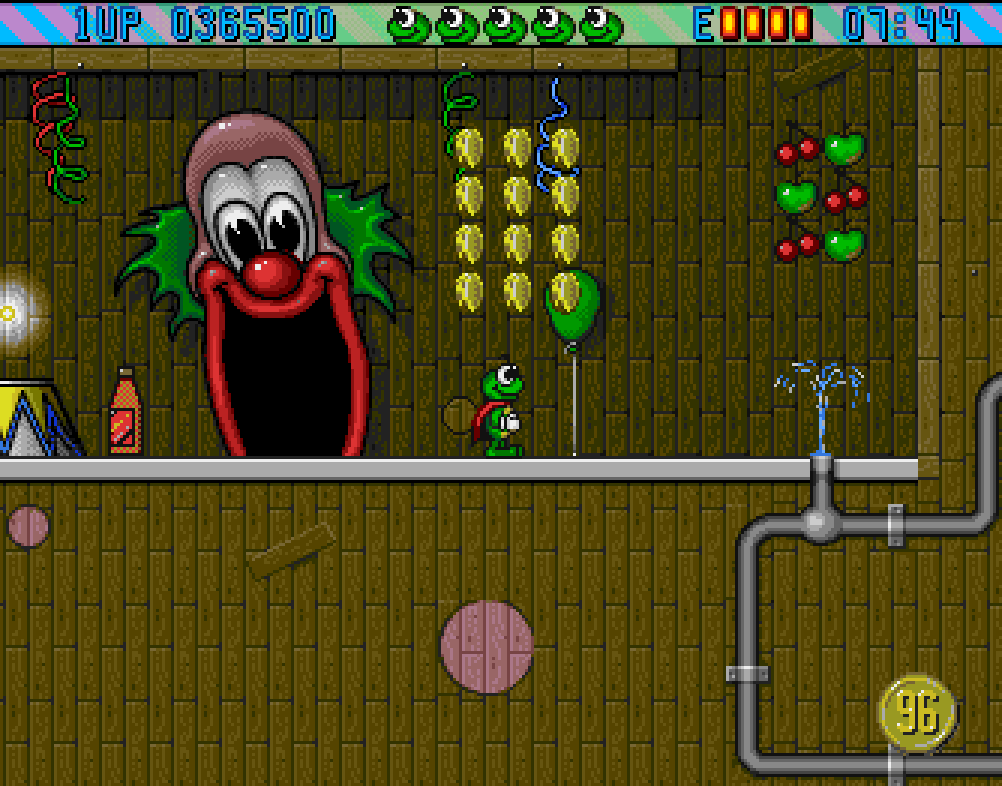

Superfrog's level design was far more than just a colorful backdrop—it was part of the experience. Each world brought its own set of aesthetics, mechanics, and atmosphere, giving players a fresh flavor with every new stage. The game was divided into six distinct zones, each with four levels, and they weren’t just reskins. They were uniquely crafted to evoke mood, challenge, and curiosity.

The opening world, the Enchanted Forest, was a lush, green playground designed to introduce players to the game’s mechanics gently. Vines, hidden tunnels, and bouncy mushrooms set the tone early. But by the time you reached the Castle, things got darker and more complex. Crumbling bricks, swinging axes, and lava pits pushed your reflexes and memory to the limit.

The Circus World added comedic elements, like spring-loaded platforms and oversized toys, while Egyptian Ruins introduced spike traps, scorpions, and sandy mazes. The final world, the Haunted Castle, dialed up the tension with more vertical platforming, tighter spaces, and a sense of foreboding—all while maintaining a cartoonish charm.

These zones weren’t just visually distinctive—they also added gameplay variation. Enemy types, environmental hazards, and secret room styles shifted dramatically. Some stages were more open and exploratory, while others were linear gauntlets. The shift between speed-focused levels and those that encouraged slow, methodical exploration was key to maintaining pacing.

The graphical work by Rico Holmes was impressive. Even without modern lighting or parallax effects, the use of shading, vibrant colors, and smooth animation gave each world its own personality. On the Amiga, this level of polish was rare—and Superfrog wore it proudly.

The Music of Superfrog: Catchy, Quirky, and Timeless

The soundtrack of Superfrog might just be its most enduring legacy. Composed by the legendary Allister Brimble, the game’s music was instantly catchy, highly melodic, and perfectly matched to the tone of each level. It wasn’t just background noise—it was mood-setting magic.

Each world had its own theme, designed to match the pace and atmosphere of the setting. The Enchanted Forest tune was upbeat and whimsical, perfect for bouncing through greenery and exploring the first levels. The Circus tracks had that manic energy you’d expect from a world filled with trampolines and clowns. And the Castle music? A little more tense, a little darker, but never too grim. Always playful. Always toe-tapping.

What made the soundtrack so remarkable wasn’t just the composition—it was how well it made use of the Amiga’s sound hardware. Brimble squeezed every ounce of musicality out of those four audio channels, layering melodies, basslines, and percussion in a way that gave the illusion of far more complexity than the hardware should’ve allowed. Even players who moved on from the Amiga still remember those tunes years later—and for good reason.

It wasn’t all just energetic platforming music, either. The intro cutscene had its own score, carefully synced with the animation to build a Saturday-morning-cartoon vibe. The slot machine minigame? Light, silly background music that felt like it belonged in a retro casino.

Many fans still revisit the soundtrack today, whether through remixes, covers, or original audio rips. It stands alongside Shadow of the Beast, Turrican, and Zool as one of the finest audio achievements of the Amiga era.

Amiga vs. CD32: Enhancements and Limitations

While Superfrog was originally released for the Amiga 500, it quickly found its way to other formats—most notably the Amiga CD32, Commodore’s ill-fated attempt at a CD-based console. The CD32 version of Superfrog was technically enhanced, though the improvements were relatively minor and didn’t fundamentally change the core experience.

The CD32 edition added CD-quality audio, including the same iconic soundtrack remastered for Red Book Audio. The improvement was subtle but noticeable. Gone were the crunchy 8-bit-like synths—in their place were cleaner, fuller tracks that maintained the spirit of the original while adding a layer of depth. Cutscenes were also slightly cleaner, with better playback quality thanks to the CD format.

However, outside of audio enhancements and some minor menu polish, the core gameplay remained untouched. The visuals, level layout, and controls were identical to the floppy disk version. Some critics questioned whether this justified a re-release, but for many fans—especially those who missed the game on its first run—it was a welcome addition to the growing (if short-lived) CD32 library.

It’s also worth noting that Superfrog made its way to MS-DOS PCs, bringing the title to a wider audience beyond the Amiga scene. This version retained much of the original’s charm but didn’t always handle as smoothly depending on the hardware. Some music and control quirks crept in, and the game’s overall presentation felt slightly “off” compared to the Amiga experience.

What remained consistent across all versions, though, was the heart of the game. The humor, the bounce, the speed—all of it survived the transition. Even without major upgrades, Superfrog on CD32 stood as proof that a well-crafted game doesn’t need to be remade to stay fun.

The 2013 HD Remake: Faithful Tribute or Missed Leap?

In 2013, Team17 surprised long-time fans by reviving Superfrog in a high-definition remake for PC, PlayStation 3, and PS Vita. The idea was promising—a modern reimagining of the original game, with updated visuals, reworked controls, and a level editor. For fans who’d grown up leaping through Amiga levels, it sounded like a dream. But the reality? A little more complicated.

Visually, the game had undergone a complete overhaul. The environments were cleaner, more detailed, and higher-res. But something crucial was missing—personality. The hand-crafted charm of the pixel art had been replaced by generic vector-style graphics that lacked the whimsy of the original. Superfrog himself looked oddly smooth, less like a storybook hero and more like a clipart mascot.

Mechanically, the game was faster but floatier. The weight and responsiveness of the original jumps were altered. This might have been a deliberate choice to appeal to modern platformer fans, but it alienated many old-school players who had muscle memory tied to the original’s precise physics.

The new levels were mixed in quality. Some were clever updates; others felt padded or uninspired. The inclusion of a level editor was a neat touch, but it didn’t gain much traction with the community. Ultimately, the remake felt more like an experiment than a celebration.

Critics were lukewarm. Some praised the effort and accessibility, while others pointed out the tonal disconnect and awkward mechanics. The remake was pulled from digital storefronts just a few years later—quietly and without much fanfare.

For diehard fans, it was a bittersweet reminder: some classics are best left in their original pixelated glory.

Critics’ Impressions Then and Now

When Superfrog first released in 1993, it was met with mostly glowing reviews from the gaming press. Magazines like Amiga Format, CU Amiga, and The One praised its smooth controls, colorful visuals, and clever level design. At a time when the platformer genre was oversaturated, Superfrog stood out not because it reinvented the formula, but because it delivered the familiar with polish, charm, and surprising depth.

Reviewers consistently highlighted the game’s balance between speed and exploration, noting that while it was clearly influenced by Sonic the Hedgehog, it never felt like a direct copy. They applauded its hidden paths, verticality, and replay value. The end-of-level slot machine received special mention as a creative reward system that added an extra layer of motivation. The music was universally praised—Brimble’s soundtrack was recognized as one of the Amiga’s best.

Over time, Superfrog earned a kind of retro royalty status. It was frequently included in “Top Amiga Games” lists and became one of the most fondly remembered platformers from the era. It was the kind of game people didn’t just play—they remembered playing it, from the Lucozade-powered intro to the castle bosses and beyond.

In more recent retrospectives, however, the tone has shifted slightly. While still respected, Superfrog has come under fair critique for its occasional control stiffness, imprecise hitboxes, and the sometimes harsh time limits. It’s recognized as a product of its era—brilliant in context, but not always forgiving by modern standards.

Still, even today, many reviewers and retro enthusiasts regard Superfrog as a high point in the Amiga library. It didn’t change the genre, but it defined a moment—and that’s just as valuable.

Why Retro Fans Still Talk About Superfrog

Among Amiga fans, Superfrog is something of a mascot—not just in the literal sense, but spiritually. It represents what was possible when talented developers poured their heart into a game on limited hardware. It showed that you didn’t need corporate backing or console muscle to create something timeless—you just needed good design, personality, and a little bit of bounce.

The fanbase surrounding Superfrog has remained remarkably active for such a niche title. Enthusiasts have preserved the game through Amiga emulators, allowing modern players to experience it exactly as it was in 1993. Online forums still share high scores, hidden secrets, and rare facts about development history. Some even create Superfrog fan art or hand-pixelated remakes that stick closer to the original than the 2013 version ever did.

The game is often cited in retro discussions about what made the Amiga special. While PC and console players were drawn to titles like Commander Keen or Donkey Kong Country, Amiga users had Superfrog—and it held its own. The smoothness, the tone, and the soundtrack made it iconic within that world.

Some retro gaming YouTubers and Twitch streamers still include Superfrog in their retrospectives or live plays, often introducing the game to younger audiences who missed its initial run. Its visibility may have faded in the mainstream, but within retro circles, it still hops proudly alongside the greats.

It's the kind of game that may not get name-dropped in every gaming documentary—but when it does get mentioned, the people who remember it? They smile. And then they hum the soundtrack.

Not Quite Sonic: The Speed Debate

Any discussion about Superfrog inevitably brings up the comparisons to Sonic the Hedgehog—and it’s not hard to see why. The momentum-based movement, the springboards, the loops, the pacing—it all invited the analogy. But here’s the thing: Superfrog was never really trying to be Sonic. It just happened to share a few surface traits.

Where Sonic was designed around blazing through levels with minimal backtracking, Superfrog encouraged players to slow down and explore. Hidden passageways, vertical climbs, secret doors—these were fundamental to the game. Rushing blindly often meant missing out on huge chunks of content or falling into death traps. Speed was rewarded, but only after careful observation. This gave the game a very different rhythm from the chaos of Sonic or the strict timing of Mario.

Critics who judged Superfrog as a “Sonic clone” often missed this nuance. It wasn’t about style over substance. It was about blending pace and puzzle, encouraging discovery while still delivering quick, responsive movement. Yes, you could bounce through levels fast, but you’d almost always miss half the fun if you did.

The game’s control system also leaned more into precision than velocity. Jumps had weight, and while Superfrog could get moving fast, his handling was tighter than Sonic’s, which often felt like controlling a pinball. This made tricky sections more manageable and allowed for platforming that required thought—not just reflexes.

So no—Superfrog wasn’t trying to out-Sonic Sonic. It was doing its own thing. And for those who appreciated that slower, more deliberate platforming with a cheeky personality, it offered a more balanced experience.

The Mascot Between the Giants

In the grand platforming arms race of the early 1990s, mascots were everywhere. Sonic was Sega’s blue blur, Mario was Nintendo’s enduring hero, and others like Zool, Bubsy, and Jazz Jackrabbit all tried to stake their claim. But Superfrog? He was different. He wasn’t loud, edgy, or overly energetic. He was kind of… wholesome.

While other mascots chased trends or tried to win over teen audiences with “attitude,” Superfrog leaned into a kind of storybook simplicity. He was a prince, turned into a frog, given magical powers by an energy drink, and sent to rescue his princess from an evil witch. Ridiculous? Maybe. But also endearing. He wasn’t trying to be a brand—he was just trying to hop to the end of the level.

He also wasn’t heavily merchandised or given sequels. That lack of oversaturation probably helped preserve his charm. Superfrog never became a punchline like Bubsy. He never outstayed his welcome. He arrived, impressed, and hopped away before things could sour.

In the platforming hall of fame, Superfrog may not be the biggest name. But among those who played him, he left an impression. He showed that sometimes, all you need is great design, solid music, and a little green guy with a cape to make a classic.

Still Hopping After All These Years

Superfrog might not have spawned a franchise or changed the face of gaming, but in the world of retro platformers, few titles have aged with as much understated charm. It was a product of its time—brimming with heart, humor, and technical brilliance—but it also offered something timeless: clean, creative, satisfying gameplay.

For those who lived through the Amiga’s golden years, Superfrog was more than a mascot. He was proof that even in a world dominated by consoles, the home computer scene could deliver magic. And for new players discovering him through emulation or retro collections, he’s a reminder that beneath the simplicity of old-school design lies a complexity and craftsmanship worth appreciating.

He may not wear the crown in the platformer kingdom, but he certainly earned his cape.

Superfrog – Game Details

-

Genre: Platformer

-

Release Year: 1993

-

Platforms:

-

Original: Amiga, CD32

-

Later Ports: MS-DOS

-

Remake (Now Delisted): Windows, Android, iOS – via Superfrog HD (Team17, 2013–2016)

-

-

Developer: Team17

-

Publisher: Team17

-

Game Engine: Custom Amiga engine

-

Age Rating: Unrated (pre-ESRB)

-

Player Modes: Single-player

-

Awards/Nominations: Frequently praised as one of the best Amiga platformers of the early ’90s