In the heart of Osaka during the late 1970s, long before the internet transformed how games were distributed and globalized, a company quietly began its journey—one that would eventually redefine the Japanese gaming industry. That company was Capcom, a name now synonymous with industry-defining titles like Resident Evil, Street Fighter, and Mega Man. But the rise of Capcom wasn’t overnight, and it certainly wasn’t without conflict, creativity, or controversy.

Capcom’s story begins not with consoles or characters, but with Kenzo Tsujimoto, a businessman with a bold vision. Before founding Capcom, Tsujimoto had already been active in the electronics sector. He started I.R.M. Corporation in 1979, focusing on the manufacturing and distribution of arcade machines, which were booming across Japan at the time. The name “Capcom” would emerge a few years later as a contraction of “Capsule Computers,” referring to their original arcade-focused development units—compact, self-contained gaming systems. The company officially took on the name Capcom Co., Ltd. in 1983.

At the time, video games in Japan were still a niche interest, though growing rapidly. Most games came from companies like Namco or Sega, but Capcom took a different approach: crafting games with distinct characters, innovative gameplay systems, and tight controls. The early years were more about survival than glory. Cash flow was unstable, and competition was fierce. But Tsujimoto had an instinct for timing and talent. He began recruiting young programmers and designers with fresh ideas—many of whom would go on to become legends in their own right, including Tokuro Fujiwara, Yoshiki Okamoto, and Shinji Mikami.

The company’s Osaka roots would go on to shape its working culture—a mix of corporate discipline and creative chaos. Unlike Tokyo-based giants like Nintendo or Sony, Capcom retained a scrappier, more personal feel in those years. That spirit bled into their games: quirky, stylized, but always polished.

What followed over the next four decades was a series of expansions, reinventions, and sometimes missteps that made Capcom one of the most influential and resilient developers in the world. From pioneering the survival horror genre to dominating arcades with fighting games, Capcom didn’t just keep up with the industry—they helped define it. But behind every franchise success was a risky pitch, a troubled production, or a visionary who fought to get their idea made.

This is the story of how a small Osaka manufacturer transformed into a global powerhouse. Not just through technical innovation or marketing—but through a relentless commitment to character, creativity, and challenge.

Founding and Early Years (1979–1983)

Capcom’s earliest chapter actually begins with I.R.M. Corporation, founded in May 1979 by Kenzo Tsujimoto, a name every Capcom enthusiast should know. Tsujimoto had already been operating a company called Irem Corporation, which was also involved in arcade machines. In a somewhat unusual move, while still president of Irem, he created a new company—one focused more aggressively on original arcade games and in-house development. This new company, I.R.M., would eventually become Capcom.

By 1981, I.R.M. had shifted its operations toward creating proprietary gaming hardware, and in 1983, the company was officially rebranded as Capcom Co., Ltd. That same year, they released their very first video game, Little League, a baseball-themed arcade title. Though modest, it marked the company’s commitment to developing its own games, rather than simply manufacturing arcade cabinets.

The term “Capsule Computers”, from which the name Capcom is derived, was meant to evoke a sense of contained, highly-polished entertainment—clean, controlled, and compact experiences. It reflected Tsujimoto’s desire to differentiate his company from the growing home computer trend in Japan. Capcom wasn’t just offering software—it was offering a complete package.

Early in this period, Capcom also began building a solid in-house development team. They moved away from subcontracting, unlike many contemporaries, and this would prove vital to their long-term success. By nurturing a core team of designers and programmers, they created a foundation for consistency and innovation.

Still, the early years weren’t easy. The Japanese arcade market was crowded and volatile, and many companies collapsed under the pressure. Capcom survived by playing smart—focusing on quality, hitting the right arcade trends at the right time, and slowly building a catalog of games that delivered reliable revenue.

The real turning point came in 1984, when Capcom released a title that would put them on the map for good.

Arcade Success and Iconic Franchises (1984–1990)

Capcom’s breakout came with the release of Vulgus in 1984, but the company really made its name with 1942—a vertically scrolling shooter set during World War II. 1942 was a commercial hit, particularly in arcades outside Japan, and became Capcom’s first major franchise. It introduced the now-classic "looping" mechanic, allowing players to dodge enemy bullets by flying backward over their plane. It was simple, addictive, and globally marketable.

This era also saw the debut of Tokuro Fujiwara, one of Capcom’s most influential early designers. Fujiwara had an uncanny sense for action mechanics and level pacing. He would go on to design several of Capcom’s major early hits and lay the groundwork for future classics.

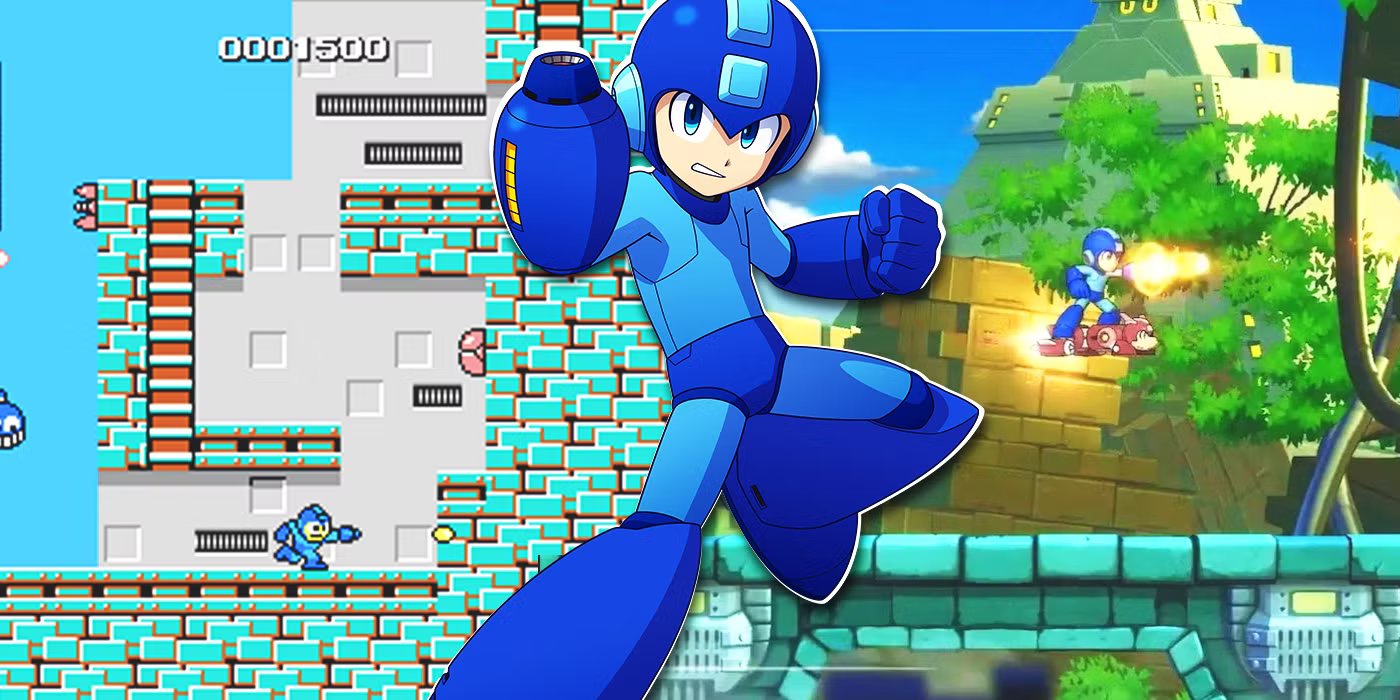

But it was in 1987 that Capcom truly hit gold. That year saw the launch of the first Mega Man (Rockman in Japan), a side-scrolling platformer with bright visuals, innovative power-copying mechanics, and a memorable blue protagonist. Created by Keiji Inafune, Mega Man became a defining icon for the company and spawned one of the most prolific series in gaming history.

Also in 1987, Capcom released Street Fighter. While the original game was not a massive success, it introduced the concept of unique characters with signature moves—setting the stage for something much bigger just a few years later.

Arcades were the beating heart of the 1980s gaming scene, and Capcom knew how to capture attention. Their cabinets were known for responsive controls, colorful sprites, and unforgettable audio. Titles like Commando, Ghosts 'n Goblins, and Final Fight followed in quick succession, building a deep bench of IPs that would be revisited and reinvented for decades.

During this time, Capcom began to expand internationally, opening subsidiaries in the United States and Europe. This move proved crucial for market testing and long-term global success. Unlike some Japanese companies that struggled to localize their content, Capcom actively tailored its games for overseas audiences—an approach that widened its appeal early on.

By the end of the '80s, Capcom had established itself as a creative powerhouse in arcades and was now eyeing the booming home console market. With Nintendo’s Famicom (NES) dominating households in Japan and North America, Capcom began a transition that would take them from the noisy glow of the arcade to the quiet focus of the living room—bringing with them all the action, challenge, and character they were known for.

Expansion into Home Consoles (1985–1995)

As the home console market surged in the mid-1980s, Capcom recognized an opportunity that many arcade-first companies initially overlooked: the living room was the future of gaming. The Nintendo Famicom (known as the NES in North America) had become a household name, and Capcom quickly adapted, forging a strong partnership with Nintendo to bring their arcade titles to consoles.

One of the first major successes in this space was the Mega Man series. While the original Mega Man in 1987 sold modestly, its sequels, especially Mega Man 2 in 1988, exploded in popularity. Not only did it improve gameplay and graphics, but it also solidified Capcom’s identity as a developer capable of translating arcade-style excitement into console masterpieces.

Capcom didn’t just port its arcade games; it tailored them. DuckTales (1989) is a standout example. Based on the Disney animated series, it became one of the most critically acclaimed platformers on the NES—not just for its polished mechanics, but for its music, level design, and the now-famous “pogo jump” mechanic. The company went on to develop several other beloved Disney games, including Chip 'n Dale Rescue Rangers and Aladdin, establishing a reputation for high-quality licensed titles.

Behind the scenes, Capcom was evolving structurally. The Osaka headquarters remained the creative core, but the newly formed Capcom USA began taking more initiative in shaping game content and marketing strategies for Western audiences. This two-pronged approach helped the company grow both globally and creatively.

Capcom also began investing in early 16-bit development for the Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis. The Street Fighter II phenomenon would hit arcades in 1991, but its home console version in 1992 was a defining moment for Capcom. Selling millions of units, it not only boosted the SNES’s global dominance but also proved that complex arcade games could thrive in homes without compromise.

By the mid-1990s, Capcom had firmly established itself as a major player across both arcade and console ecosystems. Its library of characters—Mega Man, Ryu, Arthur, Final Fight’s Cody and Guy—had become instantly recognizable. But just as important, Capcom had shown it could adapt and evolve. That would be crucial heading into a new decade, where the stakes would rise dramatically—and a new genre would be born.

Pioneering the Survival Horror Genre (1996–2000)

Few companies can claim to have invented a genre, but Capcom did exactly that with the release of Resident Evil in 1996. The game, directed by Shinji Mikami, wasn’t the first horror game ever made—but it crystallized the formula: limited resources, fixed camera angles, tense pacing, and a mansion full of unspeakable horrors. It coined the term “survival horror”, and in doing so, sparked one of the most enduring franchises in gaming history.

Resident Evil (Biohazard in Japan) was more than a technical achievement; it was a tonal shift for Capcom. Previously known for bright, action-heavy games, this title showed they could create atmosphere, tension, and cinematic storytelling. The game’s success led to multiple sequels, spin-offs, films, and an entire generation of horror-inspired game design.

Mikami, who had worked under Tokuro Fujiwara (the creator of Ghosts 'n Goblins), became one of Capcom’s most important creative forces. Under his direction, Resident Evil 2 (1998) pushed character drama and visual fidelity even further. Resident Evil 3 and the Code: Veronica side story continued expanding the series' lore and audience reach.

But Capcom didn’t stop with survival horror. This era also saw the creation of Devil May Cry—originally intended as Resident Evil 4, the project took on a life of its own under Hideki Kamiya, turning into a high-octane, gothic action title that would inspire countless imitators. While Devil May Cry would be released in 2001, its foundation was laid during this creatively fertile period.

Meanwhile, Capcom was experimenting with 3D in other areas. Dino Crisis (1999) took the survival horror blueprint and swapped zombies for velociraptors. It may not have reached the same iconic status, but it showed Capcom’s willingness to iterate and expand genre boundaries.

Fighting games remained strong as well. Capcom launched Marvel vs. Capcom in 1999, further expanding the Street Fighter universe and building partnerships with external brands in ways few other companies attempted at the time.

By the turn of the millennium, Capcom was a company in creative overdrive. With a growing library of franchises, international success, and major talent rising within its ranks, it seemed poised to dominate every genre. But success brought its own challenges—both creatively and corporately.

Diversification and New IPs (2001–2010)

The early 2000s marked a transitional period for Capcom, one full of innovation, experimentation, and internal risk. With the PlayStation 2, GameCube, and Xbox ushering in a new era of console power, Capcom leaned heavily into developing original IPs and expanding existing franchises into bold new directions.

Devil May Cry (2001) led the charge with fast-paced, stylish combat that defined a subgenre of action games. Its protagonist, Dante, became an instant icon—cocky, acrobatic, and unforgettable. This wasn’t just a new series—it was a new identity for Capcom, blending horror aesthetics with arcade-style reflex gameplay.

Another standout from this era was Viewtiful Joe (2003), a stylized side-scroller that embraced both 2D nostalgia and modern polish. Developed by the newly formed Clover Studio, Viewtiful Joe highlighted Capcom’s willingness to bet on creative teams with distinct voices. Clover would go on to produce Ōkami and God Hand, beloved by critics and niche fans, but ultimately not major commercial hits—leading to the studio’s closure in 2007.

Perhaps Capcom’s biggest success story of the decade was Monster Hunter (2004). Though initially slow to catch on outside Japan, it became a cultural phenomenon domestically, with players linking up via PSPs to take down massive creatures in tactical multiplayer hunts. The franchise would eventually explode internationally—but even in its early days, it was clear Capcom had something special.

This period also saw Capcom branching into online and multiplayer experimentation—sometimes with mixed results. Games like Lost Planet, Dead Rising, and Onimusha received praise for their ambition, but struggled with consistency. Still, these titles expanded Capcom’s technical reach and demonstrated a willingness to take risks.

Internally, the company faced some corporate restructuring and changing leadership dynamics. Several key developers, including Keiji Inafune, expressed frustration with bureaucracy and creative stagnation. Inafune would later leave the company in 2010, citing a need for more freedom to pursue bold ideas.

Despite these challenges, Capcom’s IP portfolio had never been more diverse. From platformers and fighters to horror and hack-and-slash, it was clear the studio wasn’t content with sticking to one genre. But cracks were beginning to show—and by the end of the decade, Capcom would face one of its toughest eras yet.

Challenges and Restructuring (2011–2015)

The years following 2010 were complex and at times uncomfortable for Capcom. Though its portfolio of franchises was broader than ever, the company faced growing criticism from fans, disappointing sales on several major titles, and internal shakeups that rattled its creative foundation. This period marked a critical juncture—one that would test Capcom's ability to adapt to a rapidly evolving industry.

One of the most visible turning points was the departure of Keiji Inafune in 2010. A central figure at Capcom since the '80s, Inafune had played major roles in Mega Man, Onimusha, Dead Rising, and Lost Planet. His exit came with pointed words about Japan's game development scene, which he saw as stagnant and risk-averse. His absence left a creative vacuum and symbolized deeper unrest within Capcom’s corporate structure.

Meanwhile, some of Capcom’s most beloved franchises were suffering. Resident Evil 6 (2012) was a commercial success but drew criticism for its action-heavy direction, veering too far from its survival horror roots. Fans who had grown up with the atmospheric dread of Resident Evil 1 and 2 were disappointed by the game's tone, which felt closer to an over-the-top action film than horror.

Capcom also misjudged its Western audience in several key releases. DmC: Devil May Cry (2013), developed by British studio Ninja Theory, attempted to reboot the franchise with a grittier tone and reimagined characters. Though praised by some critics, the game's new direction alienated many longtime fans of the series. It reflected a broader issue: Capcom was struggling to balance its Japanese identity with a desire to appeal to Western markets.

Adding to this was the company’s increasing reliance on DLC models and controversial business practices. On-disc DLC (downloadable content that players had to pay to unlock despite already owning it physically) in games like Street Fighter X Tekken sparked outrage. Capcom's image took a hit, with many accusing the company of prioritizing monetization over player trust.

Financially, things were tight. Profit margins were shrinking, and Capcom had to scale back its internal development, choosing instead to license out some of its IPs or co-develop with external partners. A leaked internal document even revealed that the company had only a few million dollars available for acquisitions or major investment—a startling figure for a studio with such a rich history.

Yet, within these challenges were the seeds of change. Capcom’s leadership began reassessing their approach, doubling down on the idea that core fans—not just global markets—were the foundation of their success. They would soon re-center their strategy around this principle, leading to one of the most unexpected and celebrated comebacks in gaming history.

Modern Era and Continued Innovation (2016–Present)

In a media landscape where companies often play it safe, Capcom's post-2015 resurgence felt like a creative rebirth. It wasn’t just about improving their games—it was about reconnecting with their roots, listening to their audience, and committing to quality and vision over compromise.

The first true signal of Capcom’s comeback was Resident Evil 7: Biohazard in 2017. Directed by Koshi Nakanishi, the game returned the franchise to its survival horror foundations, this time through a bold first-person perspective. It was atmospheric, terrifying, and masterfully paced—earning widespread acclaim and revitalizing the once-ailing franchise. The RE Engine, developed in-house for the title, became a crucial piece of Capcom’s future success.

But it was Monster Hunter: World (2018) that catapulted the company back into the global spotlight. Previously niche outside Japan, Monster Hunter finally broke through with a version built for home consoles rather than handhelds. It streamlined systems without sacrificing depth, offered seamless multiplayer, and was visually stunning. It sold over 20 million copies, making it the best-selling game in Capcom’s history and proving the studio could build global hits without abandoning its Japanese DNA.

The hits kept coming. Resident Evil 2 Remake (2019) struck the perfect balance between nostalgia and innovation. It respected the original’s legacy while updating the visuals, mechanics, and pacing for modern audiences. Resident Evil Village (2021) continued that momentum, blending Gothic horror, action, and mystery in a way that few AAA games even attempt.

Meanwhile, Capcom’s fighting game division made waves with Street Fighter V updates and competitive support—though some criticized the game's rough launch and initial content limitations. Learning from those missteps, Capcom prepared Street Fighter 6 with renewed attention to polish and accessibility, launching it in 2023 to widespread praise.

What makes this period remarkable is not just the success—it’s how deliberate it was. Capcom focused on its strongest franchises, modernized its internal tech with the RE Engine, improved transparency with fans, and invested in tight, genre-focused experiences that delivered both creatively and commercially.

Capcom also embraced digital platforms more fully, improving PC releases, enhancing localization, and offering consistent content across platforms. Their legacy remakes—Resident Evil 3, Mega Man Legacy Collections, Ace Attorney Chronicles—further deepened fan engagement while introducing new audiences to classic titles.

In less than a decade, Capcom had gone from a company riddled with doubt and missteps to one of the most respected and consistent publishers in the industry. Their renaissance wasn’t about following trends—it was about returning to their core identity and refining it for a new era.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

Capcom’s legacy is more than just a list of iconic games—it’s a story of influence, reinvention, and creative bravery. From arcades to consoles, from the horror genre to fighting game tournaments, Capcom has shaped not just what games can be, but how they're remembered.

Think of the characters they’ve given the world: Ryu, standing stoic in every generation of fighters. Mega Man, the embodiment of challenge and perseverance. Leon Kennedy and Jill Valentine, battling zombies and conspiracies across decades. These aren’t just game protagonists—they're cultural landmarks.

Street Fighter II helped birth the competitive fighting scene. It laid the groundwork for esports before the term even existed. Today, tournaments like EVO and the Capcom Pro Tour draw international crowds, with professional players making careers out of the depth and balance that Capcom’s mechanics offer.

Resident Evil didn’t just define a genre—it influenced film, television, literature, and even real-life emergency training simulations. Monster Hunter, once a phenomenon limited mostly to Japan, has become a global success story, blending co-op play with social experiences in a way few other franchises achieve.

Capcom’s influence extends to game design philosophy, too. Their “learn through failure” approach, precise control systems, and tight pacing have been studied and emulated by countless developers. Their IPs have stood the test of time not because they were easy or flashy, but because they were fundamentally sound—and made with care.

And through it all, they’ve stayed distinct. Capcom isn’t just a brand—it’s a signature. A style. A risk-taker. An innovator. A developer that, even after four decades, still believes in surprising players, testing their skills, and giving them worlds they want to return to.

Capcom’s journey—from Osaka startup to global titan—hasn’t been smooth, but it’s been undeniably remarkable. Not because they never failed, but because they always came back stronger, smarter, and more committed to what made them special in the first place.