In 1993, the video game world was saturated with side-scrolling platformers. But few had the backing, charm, or cinematic polish of Disney’s Aladdin on the Sega Genesis. Developed by Virgin Games in collaboration with Disney, this version of Aladdin wasn't just another licensed tie-in—it was a technological and artistic leap that stunned players and critics alike. For the first time, it felt like a game truly looked and moved like an animated film.

At the center of this achievement was a rare partnership: actual Disney animators were brought in to create the character frames. These weren’t reinterpretations by game artists—they were literal hand-drawn frames scanned directly into the game using a technique called “Digicel,” developed by Virgin’s animation team. This gave Aladdin a visual style that hadn’t been seen before on a home console. The movement, expressions, and fluidity of the characters rivaled anything players had seen up to that point.

The collaboration came with risk. Disney was known for being highly protective of its properties, and the idea of lending their animators to a video game was uncharted territory. But the gamble paid off. Led by programmer David Perry, the Virgin team created a game that wasn’t just beautiful—it was tightly constructed, deeply playable, and faithful to the spirit of the animated movie without simply rehashing it.

The result was more than just a licensed game. It became one of the defining platformers of its generation, proving that film and video game studios could work together to create something truly exceptional.

Innovative Animation Techniques: Bringing Agrabah to Life

The most striking feature of Aladdin on the Genesis was its animation. Even today, players still marvel at how well it captured the fluidity and expressiveness of Disney’s 1992 animated film. This was largely thanks to the implementation of the “Digicel” process, which essentially involved traditional hand-drawn animation being digitized and imported into the game engine.

This wasn’t just sprite work—it was frame-by-frame animation done by Disney animators who had worked on the actual movie. That level of authenticity gave Aladdin a leg up on nearly every other platformer of the era. Every character had a personality that came through in the animation—whether it was the way Aladdin swung from poles with a smirk or the bounce in his step as he tossed apples at guards.

The backgrounds were equally impressive. Marketplaces bustled with visual detail, desert levels shimmered with heat, and palace interiors glowed with golden opulence. The environments didn’t just look good—they felt alive. Each level was a stylized canvas, brimming with subtle animations, from flying carpets in the background to barrels wobbling precariously atop ledges.

What made this even more impressive was how seamlessly the animation integrated with the gameplay. Often in early 90s games, beautiful visuals came at the cost of responsiveness. Not so here. The movement was tight, the hit detection solid, and the transitions between animations so clean you’d almost forget you were controlling a sprite and not a cartoon character.

This attention to animation detail gave Aladdin something many licensed games lacked—authenticity. It felt like a Disney product, not just a game with Disney branding. And that distinction still resonates with players to this day.

Platforming Through Agrabah: Level Design and Challenges

At its core, Aladdin was a 2D platformer—but it was one with surprising variety and cleverness in level design. Each stage wasn’t just a backdrop for jumping and fighting—it was a dynamic space filled with traps, secrets, and layered platforming opportunities that made full use of the game’s smooth animation and controls.

The game opened in the bustling streets of Agrabah, where players dashed across rooftops, bounced off awnings, and dodged market vendors’ thrown items. It immediately set the tone: this wasn’t a slow-paced platformer—it was kinetic, playful, and packed with energy. Enemies were smartly placed, and hazards were tied closely to the theme of the level. Flying pots, roaming guards, and even mischievous monkeys created environmental variety and tension.

As the game progressed, players ventured into the Cave of Wonders, a more vertical and perilous area filled with collapsing platforms, fire traps, and deadly lava pits. This section in particular showed off the game’s ability to shift its mood from playful to serious without losing its pacing. The lava escape sequence, complete with fast scrolling and twitch-based timing, was a standout moment that still gets cited in retrospectives today.

Later stages, like the Sultan’s Dungeon and the Genie’s Lamp, introduced surreal and comedic elements. In the lamp world, platforms floated freely in space, with the Genie’s giant hands and laughing faces forming obstacles and springboards. These imaginative touches gave the game a sense of creativity that kept things from ever feeling repetitive.

Difficulty-wise, Aladdin was fair but not easy. The time limits, limited lives, and tricky enemy placements ensured that players had to stay sharp. But the game never felt punishing for the sake of it. Instead, it encouraged exploration, reaction, and memory—core skills that made mastering its platforming incredibly satisfying.

Combat and Controls: Aladdin’s Swordplay and Acrobatics

One of the key features that differentiated the Genesis version of Aladdin from other platformers of the time—especially its SNES counterpart—was its inclusion of sword combat. Instead of relying solely on jumping on enemies or tossing projectiles, players could engage in direct melee battles, slicing through guards with fluid sword strikes that looked and felt dynamic.

The sword wasn’t just a gimmick. It added tactical depth to the combat. Some enemies required precise timing to defeat, while others blocked frontal attacks and had to be flanked or stunned with apples first. Aladdin's sword swings were responsive, and his animations flowed from idle to attack without delay, allowing players to chain movements in a way that felt intuitive.

In addition to the swordplay, Aladdin also had acrobatic movement that matched the tone of the film. He could leap gracefully between platforms, swing from ropes and poles, slide down slopes, and bounce off walls or canopies to reach hidden areas. These moves weren’t just cosmetic—they were often essential to survival and exploration. The level design made full use of these mechanics, challenging players to think vertically as well as horizontally.

The control scheme was tight and well-tuned. The jump arc was consistent and predictable, essential for avoiding deadly traps and nailing tough sequences. The hitboxes were generous enough to prevent frustration but precise enough to reward skill.

Together, the swordplay and platforming created a hybrid gameplay experience. You weren’t just running through levels—you were engaging with them, fighting through them, and dancing between hazards in ways that kept the momentum fast and the player in control. It was a blend of action and grace that few platformers managed to deliver at the time.

Collectibles and Bonus Stages: Enhancing Replayability

Aladdin wasn’t just a game you rushed through—it was a game that rewarded those who slowed down, explored every corner, and looked beyond the obvious path. Hidden within each level were collectibles and secret areas that added depth, variety, and genuine reasons to return for multiple playthroughs.

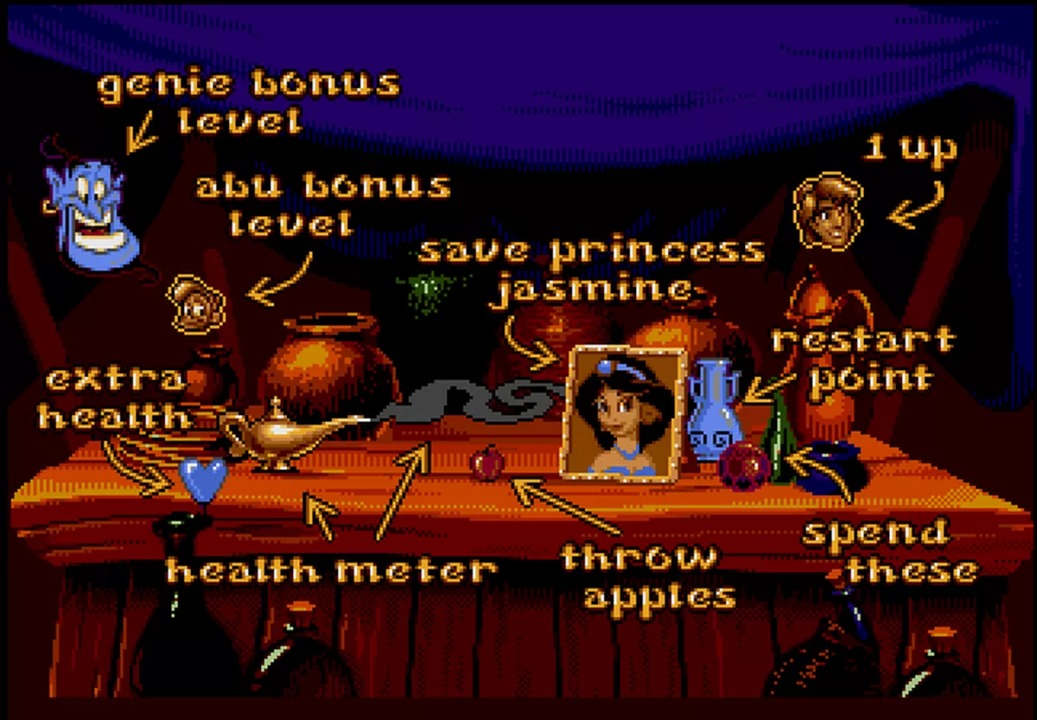

Apples were the most common item, functioning as Aladdin’s primary ranged attack. You could use them to stun enemies from a distance, giving you breathing room before engaging with your sword—or as your only defense in trickier platforming segments. While not overpowered, they offered a clever tactical alternative and made certain battles much easier when used effectively.

Gems served a dual purpose: they increased your score and functioned as a form of progression incentive. Collecting enough could unlock bonus content or lead to extra lives and continues. These gems were often placed in risky or hidden areas, encouraging players to master difficult jumps or explore off the main path.

Then there were the genie tokens, which allowed access to the game’s memorable bonus stages. These featured Abu, Aladdin’s mischievous monkey companion, in a fast-paced mini-game where you dodged falling objects to gather loot. These bonus stages were short but addictive, giving a lighthearted break from the core game’s intensity and offering meaningful rewards like continues, extra lives, and power-ups.

This system of collectibles and bonus levels helped distinguish Aladdin from more linear platformers. Instead of simply reaching the end of each level, players were encouraged to engage with the environment more fully. There was a playful joy in uncovering a stash of gems behind a false wall or discovering a tricky-to-reach genie token on the edge of a crumbling ledge.

And because many of these bonuses were subtly hidden rather than loudly signposted, each discovery felt earned. It was this layer of optional depth that gave Aladdin its staying power—inviting players to come back, again and again, not just to beat the game, but to master it.

Hand-Drawn Magic: The Artistry Behind the Sprites

One of the most enduring aspects of Aladdin’s legacy is its animation artistry. This wasn’t just a game that looked good for the time—it looked good, period. In an era when pixel art was often limited by hardware constraints, Aladdin managed to deliver visuals that felt fluid, expressive, and artistically unified across the entire experience.

The brilliance lay in the collaboration between Virgin Games and actual Disney animators. Unlike most video games, which used pixel-by-pixel sprite creation, Aladdin used hand-drawn frames—just like a traditional animated film. These were then digitized and compressed using a technique known as Digicel, allowing the Genesis to render them smoothly within the game engine.

The result? Sprites that didn’t just move—they performed. Aladdin didn’t simply jump; he crouched, pushed off, and landed with a bounce. Guards flinched and staggered when hit, throwing in comedic overreactions that mirrored the exaggerated style of the film. Even background characters had movement, whether it was a merchant waving a fist or a monkey scampering across the screen.

The visual consistency was also remarkable. Character designs matched their film counterparts almost exactly, giving players the uncanny feeling of playing an actual Disney cartoon. Genie’s smiling face in the bonus stages, Jafar’s shadowy transitions, the magic carpet’s expressive twitches—it all added up to a world that felt cohesive and genuinely magical.

Even in comparison to 16-bit contemporaries like Sonic the Hedgehog or Earthworm Jim, Aladdin stood apart for its animation quality. It wasn’t just about detail—it was about performance. Every movement had weight and intention, and every frame was designed to be part of a visual narrative.

More than just eye candy, this visual storytelling elevated the gameplay. It gave players subconscious cues, added charm, and created a sense of connection with the world that went beyond mechanics. In short, Aladdin didn’t just show Agrabah—it brought it to life.

Environmental Design: From the Streets of Agrabah to the Cave of Wonders

Each level in Aladdin was crafted not only to challenge the player but also to evoke specific moods, aesthetics, and parts of the original film’s storyline. This environmental design was a key pillar in making the game feel like more than a platformer—it felt like an interactive Disney adventure.

The Agrabah marketplace introduced players to a chaotic but vibrant world. Rooftops, street vendors, and awnings weren’t just background details—they were interactive elements, forming part of the gameplay loop. Barrels could roll down at you, baskets popped open with surprises, and windows revealed glimpses of life in the city.

Moving forward, the Cave of Wonders marked a tonal shift. The brightness of Agrabah gave way to darkness, lava, and towering treasure mounds. Here, the level design leaned heavily into verticality and precision. Platforms crumbled beneath your feet, lava geysers erupted unpredictably, and the golden glow of the background created both beauty and danger.

Then came the Genie’s Lamp, a surreal dreamscape that departed from realism entirely. Platforms floated in mid-air, physics bent themselves around absurdity, and Genie’s body parts became bouncing pads, springboards, or animated hazards. It was a level that felt more like a fever dream than a movie adaptation—and it worked beautifully.

Later levels took players to dungeons, palace interiors, and finally, the battle with Jafar—each progressively more detailed and daunting. Lighting, palette choice, and sprite density all shifted with the emotional tone of the game, helping players feel the rising tension without a single word of dialogue.

It’s rare to find a platformer from the 90s with such environmental diversity, and rarer still to find one where each level feels like a chapter—not just in gameplay, but in tone and storytelling. Aladdin succeeded not just because it looked good, but because every part of its world felt intentional, playable, and alive.

Musical Adaptations: Translating Iconic Songs into 16-Bit Scores

One of the most memorable aspects of Disney’s Aladdin on the Sega Genesis was its ability to capture the heart of the film’s soundtrack and reimagine it through the console’s limited sound hardware. This wasn’t an easy feat—taking full orchestral arrangements and transforming them into snappy, chiptune-friendly versions that could still evoke emotion and nostalgia required careful thought and technical skill.

The composer, Tommy Tallarico, was instrumental in this transformation. With creative ingenuity, he adapted several of the film’s iconic tracks—most notably “A Whole New World”, “Prince Ali”, and “Friend Like Me”—into 16-bit renditions that retained their melodic core. Each tune was composed in such a way that it matched the pacing and atmosphere of its respective level, enhancing the gameplay experience without ever distracting from it.

The Agrabah marketplace was accompanied by an energetic, percussion-heavy remix of “One Jump Ahead,” giving the opening level a playful urgency. In contrast, the Genie’s Lamp level featured a warped, surreal version of “Friend Like Me,” distorted slightly to match the visual weirdness of the stage. Even in quieter moments, the soundtrack found ways to carry emotional weight—using minor keys and ambient synths to create tension in the dungeons or during boss fights.

What’s particularly impressive is how well the Genesis' Yamaha YM2612 sound chip was utilized. Known for its FM synthesis, the chip could produce rich tones when handled by someone who understood its quirks. Tallarico clearly did. His compositions were not only technically sound, but also carried a level of craftsmanship that made the music feel less like background noise and more like an active part of the story.

Even today, retro enthusiasts remember the soundtrack fondly. It stands as proof that, with creativity and respect for source material, even limited hardware can produce audio experiences that stay with players long after the console has powered down.

Genesis vs. SNES: Comparing Two Distinct Aladdin Experiences

Perhaps no game in the 16-bit era has been more frequently compared across platforms than Aladdin. That’s because in an unusual move, Disney licensed two completely different versions of the game: one for the Sega Genesis, developed by Virgin Games, and one for the Super Nintendo, developed by Capcom. Both released in 1993. Both were critically acclaimed. But they were very different games.

The Genesis version, which this article has focused on, was more combat-oriented, featuring swordplay, lavish hand-drawn animation from Disney animators, and a fast-paced action feel. In contrast, Capcom’s SNES version featured no sword at all—Aladdin defeated enemies by jumping on them or using projectiles. The gameplay leaned more toward puzzle-platforming and acrobatics than combat.

Visually, the SNES version also took a different approach. It featured crisper pixel art, brighter colors, and tighter sprites, but it lacked the fluidity of the Genesis animation. There were no Digicel frames, and the environments, while beautifully detailed, felt more like traditional video game levels than animated film scenes.

The SNES version also made broader use of verticality and multi-directional levels. There were more sections involving climbing, hanging, and maneuvering through maze-like stages, whereas the Genesis version emphasized horizontal momentum and stylized movement.

Musically, the SNES used the console’s SPC700 sound chip, offering more sampled instrumentation. While some argue this gave the music a richer tone, others felt it lacked the raw charm and dynamism of the Genesis version’s FM synth compositions.

Ultimately, the debate over which version is superior comes down to preference. If you valued animation fidelity and action, the Genesis version reigned supreme. If you preferred tight controls, platforming puzzles, and a more traditional game structure, the SNES version delivered. What’s remarkable is that both games were so good—and yet so different—that they’ve each carved their own legacy in retro gaming history.

Other Ports and Adaptations: Bringing Aladdin to Various Platforms

While the Genesis and SNES versions were the most well-known, Aladdin also found its way to a variety of other platforms—some better than others. These ports expanded the game’s reach, but they also highlighted the limitations of hardware and the challenges of adapting such a visually rich experience to less capable systems.

The Amiga version, while based largely on the Genesis game, had several notable differences. The animation was toned down, sprite sizes were reduced, and some sound effects were missing. While still enjoyable, it lacked the fluidity and punch of the Genesis original. However, on the technical side, it was an impressive feat given the Amiga's limitations and offered a comparable experience to fans of the platform.

The DOS version, similarly, brought the game to PC users—though often with caveats. Depending on the user’s sound card and processor, performance and music quality varied wildly. Controls on keyboard weren’t always ideal, but it was still a decent port for its time.

Handheld adaptations, like those on the Game Boy and Game Gear, were significantly stripped down. They featured simplified graphics, shorter levels, and fewer mechanics. The Game Boy version in particular lacked the charm and technical prowess of its console cousins, often feeling like a placeholder rather than a true adaptation. Still, for kids on the go, it scratched the itch.

Later, the game was re-released in compilation packs and digital bundles, including the Disney Classic Games Collection for modern platforms. These versions allowed players to switch between Genesis and SNES versions, making it easier than ever to compare the two. Quality-of-life features like save states and screen filters helped modernize the experience, while preserving the core gameplay.

The wide range of ports proved one thing above all: Aladdin was in demand. And whether it was a polished console experience or a scaled-down handheld version, players were eager to jump into Agrabah however they could.

Critical Acclaim and Commercial Success

From the moment Aladdin hit store shelves, it was a massive success. On the Genesis, the game sold over 4 million copies, making it one of the best-selling titles on the platform—not just among licensed games, but across the board. For Sega, it was a triumph: a marquee game during the holiday season of 1993, riding the wave of the film’s success and demonstrating the capabilities of their console.

Critically, it was universally praised. Gaming magazines like Electronic Gaming Monthly, GamePro, and Mean Machines Sega gave it high scores across categories—graphics, sound, gameplay, and animation. Reviewers lauded the smoothness of the animation, the tightness of the controls, and the way the game managed to capture the essence of the movie without feeling like a simple cash-in.

Awards followed. It won multiple “Game of the Year” accolades in its category and was often used as a benchmark for quality in future licensed games. Importantly, it helped redefine expectations for what a movie-based video game could be. Up until then, many such games were poorly executed, rushed projects. Aladdin proved that, with care, budget, and collaboration, licensed games could be just as strong—if not stronger—than original IPs.

In the years since, Aladdin has retained a strong presence in retro gaming discussions. It consistently appears in lists of the best Genesis games, the best licensed games, and even the best platformers of the 16-bit era. Its critical legacy is well cemented—not just as a technical showpiece, but as a game that respected its players and source material in equal measure.

Aladdin in Retrospect: Nostalgia and Continued Fan Appreciation

For many who grew up in the 90s, Aladdin isn’t just a great game—it’s a formative memory. Whether it was the thrill of that first sword fight in Agrabah or the panic of escaping the Cave of Wonders on a magic carpet, the game etched itself into players’ minds not just through mechanics, but through mood, tone, and feeling. It was one of those rare licensed games that didn’t just live in the shadow of its movie counterpart—it stood proudly alongside it.

A huge part of that enduring affection comes from the game’s accessibility. You didn’t need to be a hardcore gamer to enjoy it. It wasn’t overly complex, didn’t bog you down with systems, and let you jump in and immediately feel the thrill of action. But it also rewarded mastery—with secrets to find, skills to sharpen, and new routes to discover.

Today, retro gaming communities continue to celebrate Aladdin through speedruns, remixes, and fan retrospectives. The game is regularly featured in YouTube retrospectives and Twitch marathons. Forums still debate the Genesis vs. SNES versions, and fan projects occasionally resurface aiming to reimagine or enhance the experience. It’s not uncommon to see players praising its level design alongside giants like Sonic 2, Mega Man X, or Donkey Kong Country—a testament to how beloved it remains.

Even outside the gaming sphere, Aladdin holds up as a brilliant example of how cross-media synergy can succeed. It took the strengths of animation, narrative, and interactive design, and wrapped them into one of the most polished packages of its era. For anyone who grew up with it, firing up Aladdin today is like flipping through an old photo album—it brings you back, instantly and warmly, to a simpler time when games just knew how to be fun.

Re-releases and Remasters: Keeping the Magic Alive

Thanks to a wave of nostalgia-fueled preservation, Aladdin hasn’t been left behind. In 2019, Disney partnered with Digital Eclipse to release the Disney Classic Games: Aladdin and The Lion King collection—a bundle that brought the Genesis version of Aladdin, alongside other classic Disney titles, to modern platforms including the Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, Xbox One, and PC.

This collection included multiple regional versions, development documents, visual filters, rewind options, and save-state support—making it easier than ever to enjoy the game without some of its more punishing retro limitations. The added ability to watch a full playthrough and jump in at any moment was especially handy for newer players or those looking to revisit specific moments.

Interestingly, the collection did not initially include the SNES version of Aladdin, which caused quite a stir in the community. The omission was eventually remedied in a later re-release—Disney Classic Games Collection: Aladdin, The Lion King, and The Jungle Book—which added the Capcom SNES version, offering players the full spectrum of 90s Aladdin experiences in one package.

These re-releases have done more than just make the game playable—they’ve preserved a piece of history. Many players who grew up with the game now share it with their own children, passing down a bit of digital magic from one generation to the next. The updated accessibility options also allow the game to reach wider audiences who may have found the original versions too difficult or inaccessible.

And the legacy doesn’t end with reissues. The DNA of Aladdin can be seen in modern platformers, especially those that blend tight controls with character-driven storytelling and animation. Games like Shantae, Cuphead, and Rayman Legends owe a quiet debt to the magic carpet ride that Aladdin took players on all those years ago.

Aladdin (1993) – Game Details

-

Genre: Platformer

-

Release Year: 1993

-

Platforms:

-

Genesis Version (Virgin): Sega Genesis / Mega Drive

-

Other Versions: MS-DOS, Amiga, Game Boy, Game Boy Color, NES (unofficial), Game Gear, Windows

-

Modern Availability:

-

PlayStation 4, Xbox One, Nintendo Switch, Windows – via Disney Classic Games Collection: Aladdin, Lion King, and The Jungle Book

-

-

-

Developer: Virgin Games USA (Genesis), Disney Software (DOS), other versions by different studios

-

Publisher: Virgin Interactive, Disney

-

Game Engine: Virgin’s proprietary engine; Genesis version used custom animation tools developed with Disney animators

-

Age Rating: ESRB: E (Everyone)

-

Player Modes: Single-player

-

Awards/Nominations:

-

Winner of Best Genesis Game of 1993 – Electronic Gaming Monthly

-

Praised for its groundbreaking animation and faithful adaptation of the film

-