It’s not every day a game turns your television into a comic book. In 1995, Comix Zone did exactly that—and did it with a confidence few games could match. Developed by Sega Technical Institute and released on the Sega Genesis during the console's final flourish, this beat-’em-up broke free from the genre’s growing sameness. It didn’t just deliver fights and combos—it did so inside an actual comic book. And no, that’s not a metaphor. From the panel-to-panel movement, to the sound-effect text that popped up with every punch, Comix Zone fully embraced its theme.

At the time, it was a visual stunner, but even beyond the graphics, there was something distinctly different about this game. It had style, grit, and a kind of meta-cleverness that most titles didn’t dare to attempt. You played as Sketch Turner, a comic book artist quite literally pulled into his own work. You didn’t just move through levels—you tore through pages. Enemies didn't spawn; they were drawn in by the villain, Mortus. Cutscenes weren’t between levels—they were printed in frames. That raw idea, executed with such polish and creativity, made Comix Zone an experience that was hard to forget.

It didn’t follow the rules. It was brutally tough, sometimes unfairly so, and it wrapped up quicker than players expected. But for those who really connected with it, Comix Zone became more than just a game—it was a revelation. Its style, its energy, and its refusal to play it safe earned it a place in gaming history. Years later, it’s remembered not just as a quirky experiment on the Genesis, but as one of the boldest and most creatively daring masterpieces of the 16-bit era.

Development History: The Birth of a Comic-Inspired Game

Comix Zone didn’t begin as a commercial mandate—it started as a passion project. The original idea came from Peter Morawiec, a developer at Sega Technical Institute (STI), who envisioned a game that played out like a living comic. This wasn’t a passing thought—it was fully formed enough to inspire a prototype called “Joe Pencil Trapped in the Comix Zone,” which already showed the game's defining ideas: panel transitions, meta-humor, and hand-drawn style. Sega saw potential, and what began as a quirky idea quickly evolved into a full production.

The timing, though, wasn’t ideal. It was the mid-'90s, and the Genesis was approaching the end of its life. With the Saturn looming and the PlayStation already stirring the industry into a 3D frenzy, Comix Zone was a 2D game in a market rushing toward the third dimension. But STI didn’t back down. They doubled down on their concept, pouring talent and time into creating a game that would be remembered long after its contemporaries faded.

The team faced real hardware limitations. The Genesis wasn’t designed for the kind of panel-by-panel transitions or sprite work Comix Zone demanded. But through sheer creative engineering, they made it happen. Animations were smooth, pages flipped seamlessly, and transitions carried real narrative flow. They also brought in established comic artists like Tony DeZuniga (known for work with DC Comics) to shape the visual identity of the game.

Every system—audio, visuals, gameplay—was built to serve that original idea: a comic book you didn’t just read, but fought your way through. And despite its niche success at launch, the team knew they’d created something special. It just came out a little too late for the market to notice.

Gameplay Mechanics: Navigating the Comic Panels

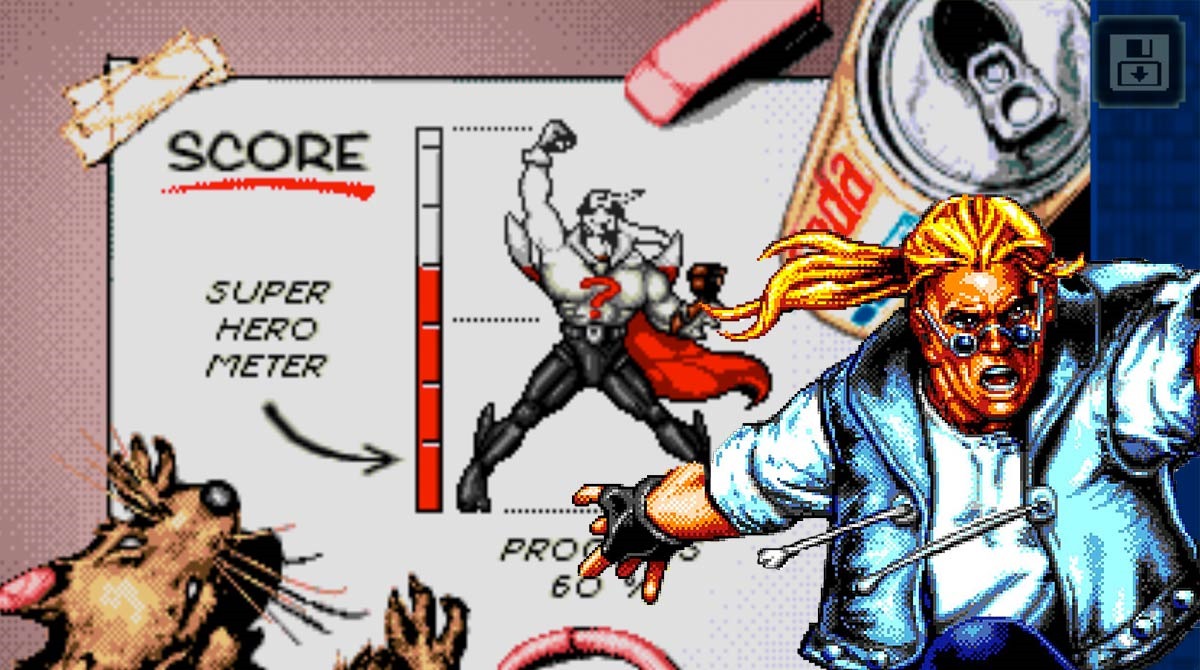

At first glance, Comix Zone might look like your standard side-scrolling beat-’em-up. But within a few seconds, it becomes clear: this isn’t a typical action game. The moment Sketch Turner crashes into the first page of his own comic, the mechanics start to shine. Levels are laid out like actual comic book pages. You move across panels, jump into frames, and fight your way to the edge—where you quite literally leap into the next part of the story.

Combat is punchy and brutal. Sketch uses a mix of martial arts moves—kicks, punches, jump attacks—and can string together light combos with satisfying weight. There’s also a wide array of items: grenades, knives, and test tubes that explode on impact. Managing these tools is critical, especially because enemies get tougher and more numerous as the game progresses.

But where Comix Zone sets itself apart is in its environmental interaction. You don’t just fight enemies—you solve puzzles. You pull switches, knock down walls, and avoid deadly traps. Your companion, Roadkill the rat, is more than a mascot. He can sniff out hidden items or activate out-of-reach levers, adding a subtle layer of problem-solving to the moment-to-moment action.

And there's a cost to exploration. Punching through barriers drains your health—a small but impactful design choice that forces players to think before smashing everything in sight. Health pickups are rare, and healing requires collecting iced tea cans (because why not?). This adds real tension to every decision. Mistakes are punished. Planning is rewarded.

With branching paths and occasional decision points, each playthrough can look a little different. But regardless of how you play, the sense of living inside a comic book remains. Panels aren’t just a visual style—they’re part of the gameplay rhythm, setting up action sequences, transitions, and even boss fights with a sense of dramatic build-up that’s unmatched in the genre.

Artistic Design: Bringing Comics to Life

It’s impossible to talk about Comix Zone without diving deep into its visual design. While other games at the time were still figuring out how to make 2D sprites look cinematic, this one just said: “Let’s make a comic.” And they did—down to the smallest details.

Each level is laid out like a two-page spread, complete with white gutters, black panel borders, and splash screens. Backgrounds are hand-drawn with exaggerated lines and bold colors, echoing the 90s comic style—somewhere between Heavy Metal and Image Comics. Characters are animated with care, each move flowing with punchy energy and comic-book flair. Even the way Sketch Turner idles or flinches feels like something pulled from an inkwell.

One of the most genius design decisions was the use of on-screen sound effects. Every major action—whether it's a punch, explosion, or kick—triggers a pop-up: “POW!”, “THUD!”, “BOOM!” These aren’t overlays; they’re in-world, jumping out of the frame like real comic effects. Speech bubbles don’t just tell the story—they also appear during fights, taunts, and scene transitions, grounding the player deeper in the narrative.

The artistic cohesion is remarkable. Every corner of this game was built with the idea that you’re not playing through a comic—you’re stuck inside one. From the paper-tearing transitions between panels to the way enemies are drawn into the scene by the villain, it all feels connected, deliberate, and alive.

There are no loading screens—just panel flips. No cutscenes—just frames filled with expressive art. And that’s what makes Comix Zone visually unforgettable. It wasn’t just good-looking for its time. It was one of the few games that built its entire identity around a single, bold concept—and absolutely nailed it.

Soundtrack and Audio: Complementing the Visuals with Grit and Groove

If the visuals of Comix Zone made it a standout title, the soundtrack gave it soul. This wasn’t just filler background music—it was a gritty, guitar-driven pulse that synced beautifully with the game’s punk-comic energy. The composer, Howard Drossin, delivered a soundtrack that felt right at home in a grungy underground zine. Each track was loud, raw, and filled with distorted energy that matched the chaos unfolding on screen.

The limitations of the Sega Genesis hardware didn’t hold it back. In fact, the FM synth gave the music its signature crunchy edge. You didn’t need a CD-quality score here—the hardware's grainy tones only made the soundtrack feel dirtier, more underground, more real. That dirty distortion became part of the game’s attitude. It didn’t need to be clean—it needed to rock.

On top of that, there was an actual CD soundtrack released alongside the game in some regions, which included real recorded instruments and vocals—a rare treat in 1995. Few games of that era went that extra mile, especially for a single title with no sequel planned. It proved that the developers knew this game deserved more than just generic tracks.

Sound effects were equally strong. Punches landed with thick, meaty thuds. Page-turning noises gave weight to the panel transitions. Explosions popped off with satisfying “BOOM!” overlays that were both visual and auditory. The feedback was constant and visceral—you could feel it all, not just see it.

Voice lines were sprinkled in sparingly but effectively. Sketch’s one-liners, Roadkill’s squeaks, enemy taunts, and Mortus’ evil cackles helped sell the atmosphere without ever feeling overused. For a 16-bit game, the sound design here was top-tier—not in terms of clarity, but in how perfectly it fit the game's identity. It was a soundtrack that didn’t just support the visuals—it completed them.

Reception and Legacy: A Cult Classic That Refused to Fade

When Comix Zone dropped in 1995, reviews were mostly positive—but cautious. Critics praised its visual style, originality, and artistic direction, often calling it one of the most unique games on the Genesis. But they didn’t shy away from pointing out its difficulty curve and short runtime. The truth is, Comix Zone didn’t arrive at the right time. The PlayStation had just launched. Gamers were looking ahead to 3D graphics and cinematic gameplay. A 2D comic brawler on aging hardware? It was easy to miss.

Yet, despite its modest commercial impact, Comix Zone didn’t disappear. Instead, it quietly gathered a cult following, a group of fans who didn’t just enjoy it—they adored it. These were the players who saw past the punishing difficulty and short length and recognized the brilliance underneath. For them, Comix Zone wasn’t a failed experiment—it was a statement.

Over the years, the game found new life through re-releases. It’s appeared on Sega Genesis Collections, emulators, Steam, Nintendo Switch Online, and more. Every time, it earns the same reaction: “Why didn’t more games do this?”

Its legacy also lives on in the games it inspired. Titles like Viewtiful Joe, Shank, and Comic Jumper owe a clear creative debt to Comix Zone. Even modern indie games with heavy stylization and meta-presentation often reflect the same DNA.

What keeps Comix Zone alive isn’t nostalgia alone—it’s admiration. It's still being discovered, played, streamed, and written about. It wasn't just another beat-'em-up. It was a game with vision—one that didn’t compromise just to follow trends. And in the long run, that’s what gave it staying power.

Challenges and Criticisms: Why It Wasn’t For Everyone

No masterpiece is perfect, and Comix Zone had its flaws—some of which were immediately noticeable even in 1995. The most prominent? Difficulty. This game is hard. Not “take your time and learn the ropes” hard—more like “good luck finishing it without memorizing every trap” hard. And it didn’t help that you only got one life. No continues unless you earned them. No save system. One bad move near the end? Back to page one.

The game’s design forced players to play cautiously, sometimes frustratingly so. Items were limited. Health was rare. Environmental damage (from breaking objects or even advancing the story) drained your life bar just as much as enemy punches. It created tension, sure—but for some players, it bordered on punishing.

Another issue was the short length. While beautifully crafted, the game only had three chapters, each split into two pages. A full playthrough, once mastered, could take under 45 minutes. For a full-priced retail game, some felt that was too lean. Replayability helped, but it wasn’t the same as having more content.

Also, the game didn’t hold players' hands. There were no tutorials, no real guidance. You either figured it out or died trying. For those who weren’t used to old-school design philosophies, it could feel more unforgiving than it needed to be.

That said, for many of us, those exact flaws became part of the game’s identity. They gave it teeth. They made beating it feel like a real victory—not just a checkpoint to check off. Still, there’s no doubt: Comix Zone was not a casual ride. It demanded patience, precision, and persistence.

The Absence of Sequels and Remakes: A Missed Opportunity

With a concept this unique and a fanbase that loved it deeply, the obvious question is: Why was there never a sequel? Why did Comix Zone never get the reboot, remaster, or spiritual successor it so clearly deserved?

The honest answer comes down to timing and priorities. By the time Comix Zone released, Sega had already shifted its focus to the Saturn and upcoming Dreamcast. 2D games, no matter how innovative, weren’t being greenlit for sequels. Comix Zone was a victim of the industry’s rapid pivot toward 3D. Had it come out just a year or two earlier—or had it been ported to the Saturn with enhancements—it might’ve had a different fate.

There have been rumors over the years—small comments from developers, brief mentions in Sega interviews—about ideas for a sequel. Concepts like a full 3D version, a crossover comic-game hybrid, or even an animated show floated around. But none ever materialized.

Strangely, even as Sega reboots or remasters other franchises, Comix Zone has been left largely untouched. No full remake, no HD reimagining. Just ports. It’s baffling, especially considering how successful modern retro-inspired titles like Streets of Rage 4 have been.

Fans haven’t given up hope, though. The demand for a Comix Zone remaster is real—and growing. With Sega now exploring more nostalgic IPs and indie-style projects, there’s renewed optimism that Comix Zone might get another shot. And if it does? It could be one of the best comeback stories in gaming.

Comix Zone’s Influence: Traces Left on Gaming Culture

Even without a sequel, Comix Zone left fingerprints all over gaming history. Its visual style and panel-based progression weren’t just impressive—they were years ahead of their time. Long before games like Viewtiful Joe, 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim, or Comic Jumper hit the market, Comix Zone laid the foundation for what a comic-inspired game could actually feel like—not just in art, but in structure.

Its influence can also be seen in how modern developers approach meta-narrative. The idea of breaking the fourth wall, of characters interacting with their medium in real time, became more common in later titles, especially in the indie scene. Think of Undertale, The Stanley Parable, or even Deadpool (the game)—they all owe something to the groundwork laid by games like Comix Zone, which wasn’t afraid to turn the format on its head.

Even stylistically, you can spot elements in everything from Shank to Cuphead, where presentation and artistic identity are just as important as mechanics. The confidence to fully commit to a visual concept—and make it part of the gameplay—was something Comix Zone proved could work. And once the industry saw that, others followed.

In the years since, Comix Zone has earned a reputation as one of Sega’s most underappreciated gems. It’s the kind of game developers cite as an influence more than fans might expect. Not because it sold millions, but because it dared to be different—and delivered.

Rediscovery on Modern Platforms

If there’s one upside to Sega’s handling of Comix Zone, it’s that they haven’t let it disappear completely. The game has been re-released multiple times, and it’s now accessible on just about every modern platform in some form. Whether it’s included in Sega Genesis Classics, Steam retro bundles, Nintendo Switch Online, or mobile ports, the game continues to reach new audiences.

And surprisingly, it holds up. The sharp art still looks great, especially with emulation filters turned off to let the crisp pixel work breathe. The combat, while simple by modern standards, remains satisfying. The soundtrack slaps as hard as ever. And the panel-to-panel traversal is still unlike anything else out there. If anything, today’s smoother hardware only enhances the transitions and responsiveness that the Genesis once struggled with.

The availability of save states in modern collections also helps fix one of the game’s biggest issues: its steep difficulty. Now, players can experiment, explore alternate routes, and truly enjoy the game without the crushing fear of permadeath. It’s a small tweak, but it makes the game far more inviting for new players.

Streaming and YouTube retrospectives have also helped revive interest. A younger generation is discovering Comix Zone through creators who highlight its artistic genius and uniqueness. These showcases often feature full playthroughs, developer trivia, and deep dives into the game’s legacy.

So while we still wait on a full-fledged remake or sequel, Comix Zone has quietly carved out a second life—and it’s one that keeps growing.

Reflection: Why Comix Zone Still Matters

There are plenty of great games from the Genesis era—Gunstar Heroes, Sonic the Hedgehog, Earthworm Jim—but few have the same kind of artistic bravery that Comix Zone brought to the table. It wasn’t designed to be another entry in a formula. It wasn’t trying to follow a trend. It had a vision—and it ran with it, even when it meant taking risks that could’ve easily backfired.

It gave us a protagonist we didn’t expect—an artist, not a warrior. It dropped us into a world where every screen had meaning. It created a vibe—punk, rough-edged, handmade—that still feels fresh today. And maybe most importantly, it refused to compromise.

Comix Zone wasn’t a game you finished casually. It fought back. It challenged you. It wanted you to feel the stress Sketch Turner felt, trapped inside his own creation, literally bleeding onto the pages of a world he drew. And because of that, every punch felt heavier. Every panel transition, more urgent. Every final boss moment, more earned.

In many ways, Comix Zone is a time capsule of bold ideas that were too good for the moment they arrived in. The industry just wasn’t quite ready. But today? It’s easy to see why so many players consider it one of the best games Sega ever made—and why those who loved it then still bring it up now.

For those of us who grew up with it, Comix Zone isn’t just a game we remember. It’s one of the games that made us love games in the first place.

Comix Zone – Game Details

-

Genre: Beat ’em up, Action

-

Release Year: 1995

-

Platforms:

-

Original: Sega Genesis / Mega Drive

-

Later Ports: Microsoft Windows, Mac OS, Linux, Game Boy Advance

-

Modern Availability:

-

PlayStation 4, Xbox One, Nintendo Switch, Windows (Steam) – via Sega Genesis Classics Collection

-

PlayStation 3 – via PSN (Digital only)

-

Xbox 360 – via Xbox Live Arcade (Digital only; region-dependent)

-

-

-

Developer: Sega Technical Institute

-

Publisher: Sega

-

Game Engine: Proprietary Sega Genesis engine

-

Age Rating: ESRB: T (Teen)

-

Player Modes: Single-player

-

Awards/Nominations: Widely recognized as one of the most innovative Sega Genesis games; featured in numerous “Top Retro Games” lists